질적 연구 설계를 위한 모델

1625년, 스웨덴의 구스타프 2세 왕은 제국주의적 목표를 강화하기 위해 네 척의 전함 건조를 명령했다. 이 중 가장 야심 찬 함선은 '바사(Vasa)'라는 이름으로, 당시 가장 큰 전함 중 하나였으며 두 개의 포갑판에 64문의 대포가 배치되어 있었다. 1628년 8월 10일, 바사는 화려하게 칠해지고 금빛 장식이 가미된 목재로 스톡홀름 항구에서 대대적인 환호와 의식 속에 진수되었다. 그러나 환호는 오래가지 못했다. 항구에 있는 동안 갑작스런 바람에 의해 배가 한쪽으로 기울며 침몰했다.

즉각적인 조사가 이루어졌고, 선체의 평형수 구획이 왕이 요구한 두 개의 포갑판을 균형 맞출 만큼 충분히 크지 않았다는 사실이 드러났다. 평형수로 사용된 121톤의 돌만으로는 배의 안정성이 부족했다. 하지만 단순히 더 많은 평형수를 추가했더라면, 하부 포갑판이 물과 너무 가까워졌을 것이다. 선박은 그 정도의 무게를 감당할 부력을 가지고 있지 않았다.

보다 일반적으로, 바사의 설계, 즉 배의 다양한 구성 요소들이 상호 관계 속에서 계획되고 건설된 방식이 치명적으로 결함이 있었다. 배는 당시의 견고한 제작 기준을 모두 충족시키며 신중히 건조되었지만, 포갑판과 평형수의 무게, 선창의 크기와 같은 주요 특징들이 서로 호환되지 않았으며, 이러한 특징들의 상호작용이 배를 전복시켰다. 당시 조선업자들은 선박 설계에 대한 일반적인 이론이 없었으며, 주로 전통적 모델과 시행착오에 의존했으며 안정성을 계산할 방법이 없었다. 원래 바사는 더 작은 배로 계획되었으나, 왕의 요구에 따라 두 번째 포갑판을 추가하면서 배가 커졌고, 이로 인해 선창에 공간이 부족해졌다(Kvarning, 1993).

바사의 이야기는 여기에서 내가 사용하는 설계의 일반 개념을 보여준다: "기능, 발전, 또는 전개를 지배하는 기본적인 계획" 및 "제품 또는 예술 작품에서 요소나 세부 사항의 배열" (Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 1984). 이것은 일상적인 의미에서의 설계를 말하며, 다음과 같은 의류 카탈로그의 인용문이 이를 보여준다:

A Model for Qualitative Research Design

In 1625, Gustav II, the king of Sweden, commissioned the construction of four warships to further his imperialistic goals. The most ambitious of these ships, named the Vasa, was one of the largest warships of its time, with 64 cannons arrayed in two gundecks. On August 10, 1628, the Vasa, resplendent in its brightly painted and gilded woodwork, was launched in Stockholm Harbor with cheering crowds and considerable ceremony. The cheering was short-lived, however; caught by a gust of wind while still in the harbor, the ship suddenly heeled over, foundered, and sank.

An investigation was immediately ordered, and it became apparent that the ballast compartment had not been made large enough to balance the two gundecks that the king had specified. With only 121 tons of stone ballast, the ship lacked stability. However, if the builders had simply added more ballast, the lower gundeck would have been brought dangerously close to the water; the ship lacked the buoyancy to accommodate that much weight.

In more general terms, the design of the Vasa—the ways in which the different components of the ship were planned and constructed in relation to one another—was fatally flawed. The ship was carefully built, meeting all of the existing standards for solid workmanship, but key characteristics of its different parts—in particular, the weight of the gundecks and ballast and the size of the hold—were not compatible, and the interaction of these characteristics caused the ship to capsize. Shipbuilders of that day did not have a general theory of ship design; they worked primarily from traditional models and by trial and error, and had no way to calculate stability. Apparently, the Vasa was originally planned as a smaller ship, and was then scaled up, at the king’s insistence, to add the second gundeck, leaving too little room in the hold (Kvarning, 1993).

This story of the Vasa illustrates the general concept of design that I am using here: “an underlying scheme that governs functioning, developing, or unfolding” and “the arrangement of elements or details in a product or work of art” (Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 1984). This is the ordinary, everyday meaning of the term, as illustrated by the following quote from a clothing catalog:

디자인은 이렇게 시작된다. 우리는 옷의 재단, 원단에 가장 잘 어울리는 바느질 스타일, 그리고 어떤 종류의 잠금장치가 가장 적합한지 등 모든 세부 사항을 신중히 고려합니다. 요컨대, 고객의 편안함에 기여하는 모든 요소를 생각합니다. (L.L.Bean, 1998)

좋은 디자인은 구성 요소들이 조화를 이루어 효율적이고 성공적인 기능을 촉진하며, 결함 있는 디자인은 부적절한 작동이나 실패를 초래합니다.

놀랍게도, 연구 설계를 다루는 대부분의 문헌은 다른 개념의 디자인을 사용합니다: "무언가를 실행하거나 달성하기 위한 계획 또는 프로토콜(특히 과학적 실험)" (Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 1984). 이러한 문헌은 설계를 연구를 계획하거나 수행하는 일련의 단계나 과제로 제시합니다. 이 설계 개념의 일부 버전은 순환적이고 재귀적이기도 하지만(예: Marshall & Rossman, 1999, pp. 26–27), 모두 본질적으로 문제의 공식화에서부터 결론이나 이론에 이르는 단방향적 순서라는 점에서 선형적입니다. 이 순서는 반복될 수 있지만, 이러한 모델은 일반적으로 시작점과 목표가 명확하고 중간 작업을 수행할 순서가 지정된 플로우차트와 비슷합니다.

그러나 이러한 순차적 모델은 질적 연구에는 적합하지 않습니다. 질적 연구에서는 연구 과정 중에 새롭게 발생하는 상황이나 다른 구성 요소의 변화에 따라 설계의 어느 구성 요소라도 재검토하거나 수정해야 할 수 있기 때문입니다. 질적 연구에서 "연구 설계는 프로젝트의 모든 단계에서 작동하는 반사적인 과정이어야 한다"(Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995, p. 24)고 합니다. 데이터 수집 및 분석, 이론의 개발 및 수정, 연구 질문의 구체화나 재초점화, 그리고 타당성 문제의 확인 및 해결 활동은 대개 거의 동시에 진행되며, 서로에게 영향을 미칩니다. 이러한 과정은 선형 모델로 적절히 표현될 수 없습니다. 비록 여러 번의 순환을 허용하는 모델이라 할지라도, 질적 연구에서는 다양한 작업이나 구성 요소들이 배치되어야 하는 불변의 순서가 존재하지 않기 때문입니다.

It starts with design. . . . We carefully consider every detail, including the cut of the clothing, what style of stitching works best with the fabric, and what kind of closures make the most sense—in short, everything that contributes to your comfort. (L.L.Bean, 1998)

A good design, one in which the components work harmoniously together, promotes efficient and successful functioning; a flawed design leads to poor operation or failure.

Surprisingly, most works dealing with research design use a different conception of design: “a plan or protocol for carrying out or accomplishing something (esp. a scientific experiment)” (Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 1984). They present design as a series of stages or tasks in planning or conducting a study. While some versions of this view of design are circular and recursive (e.g., Marshall & Rossman, 1999, pp. 26–27), all are essentially linear in the sense of being a one-directional sequence of steps from problem formulation to conclusions or theory, though this sequence may be repeated. Such models usually resemble a flowchart, with a clear starting point and goal and a specified order for performing the intermediate tasks.

Such sequential models are not a good fit for qualitative research, in which any component of the design may need to be reconsidered or modified during the study in response to new developments or to changes in some other component. In a qualitative study, “research design should be a reflexive process operating through every stage of a project” (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995, p. 24). The activities of collecting and analyzing data, developing and modifying theory, elaborating or refocusing the research questions, and identifying and addressing validity threats are usually all going on more or less simultaneously, each influencing all of the others. This process isn’t adequately represented by a linear model, even one that allows multiple cycles, because in qualitative research there isn’t an unvarying order in which the different tasks or components must be arranged.

전통적인 선형 설계 접근법은 연구 수행을 위한 모델을 제공합니다. 이는 연구를 계획하거나 수행하는 데 필요한 작업들을 최적의 순서로 배열한 규범적 가이드입니다. 이에 반해, 이 책에서 제시하는 모델은 연구를 위한(for) 모델인 동시에 연구 자체의(of) 모델입니다. 이 모델은 연구의 실제 구조를 이해하는 데 도움을 줄 뿐만 아니라, 연구를 계획하고 수행하는 데에도 도움을 줍니다. 이 모델의 본질적인 특징은 연구 설계를 단순한 추상적 개념이나 계획이 아닌, 실제 존재하는 실체로 취급한다는 점입니다.

Kaplan(1964, p. 8)이 제안한 연구의 “사용 중 논리(logic-in-use)”와 “재구성된 논리(reconstructed logic)”라는 구분을 차용하여, 이 모델은 연구의 “사용 중 설계(design-in-use)”, 즉 연구 구성 요소들 간의 실제 관계를 나타내는 데 사용될 수 있습니다. 이는 의도된(또는 재구성된) 설계와 함께 작동합니다(Maxwell & Loomis, 2002). 바사의 설계처럼, 여러분의 연구 설계도 실제로 존재하며 실제적인 결과를 초래할 것입니다. Yin(1994, p. 19)은 “모든 경험적 연구 유형에는 명시적이든 암묵적이든 연구 설계가 포함된다”고 말했습니다. 설계가 항상 존재하기 때문에 이를 명시적으로 드러내는 것이 중요하며, 이를 통해 설계의 강점, 한계, 결과를 명확히 이해할 수 있습니다.

연구를 위한(for) 모델인 동시에 연구 자체의(of) 모델로 설계를 이해하는 이러한 개념은 의과대학생들을 대상으로 한 고전적인 질적 연구에서 잘 드러납니다(Becker, Geer, Hughes, & Strauss, 1961). 저자들은 “연구 설계”에 대한 장을 다음과 같이 시작했습니다:

어떤 의미에서 우리의 연구에는 설계가 없었습니다. 즉, 테스트할 체계적인 가설이 없었고, 이 가설과 관련된 정보를 확보하기 위해 고안된 데이터 수집 도구도 없었으며, 사전에 명시된 분석 절차도 없었습니다. 설계라는 용어가 이러한 정교한 사전 계획의 특징을 암시한다면, 우리의 연구는 설계가 없었습니다.

설계를 더 크고 느슨한 의미로 이해한다면, 즉 우리의 절차에서 나타난 질서, 체계성, 일관성을 식별하는 방식으로 설계를 본다면, 우리의 연구에는 설계가 있었습니다. 우리는 문제에 대한 초기 관점, 이론적 및 방법론적 약속, 그리고 이러한 요소들이 연구 과정에서 우리의 연구에 영향을 미치고, 또한 연구에 의해 영향을 받은 방식을 설명함으로써 이것이 무엇인지 말할 수 있습니다. (1961, p. 17)

Traditional, linear approaches to design provide a model for conducting the research—a prescriptive guide that arranges the tasks involved in planning or conducting a study in what is seen as an optimal order. In contrast, the model in this book is a model of as well as for research. It is intended to help you understand the actual structure of your study, as well as to plan this study and carry it out. An essential feature of this model is that it treats research design as a real entity, not simply an abstraction or plan. Borrowing Kaplan’s (1964, p. 8) distinction between the “logic-in-use” and “reconstructed logic” of research, this model can be used to represent the “design-in-use” of a study, the actual relationships among the components of the research, as well as the intended (or reconstructed) design (Maxwell & Loomis, 2002). The design of your research, like the design of the Vasa, is real and will have real consequences. As Yin stated, “every type of empirical research has an implicit, if not explicit, research design” (1994, p. 19). Because a design always exists, it is important to make it explicit, to get it out in the open where its strengths, limitations, and consequences can be clearly understood.

This conception of design as a model of, as well as for, research is exemplified in a classic qualitative study of medical students (Becker, Geer, Hughes, & Strauss, 1961). The authors began their chapter on the “design of the study” by stating that:

In one sense, our study had no design. That is, we had no well-worked-out set of hypotheses to be tested, no data-gathering instruments purposely designed to secure information relevant to these hypotheses, no set of analytic procedures specified in advance. Insofar as the term “design” implies these features of elaborate prior planning, our study had none.

If we take the idea of design in a larger and looser sense, using it to identify those elements of order, system, and consistency our procedures did exhibit, our study had a design. We can say what this was by describing our original view of the problem, our theoretical and methodological commitments, and the way these affected our research and were affected by it as we proceeded. (1961, p. 17)

따라서 연구, 특히 질적 연구를 설계하려면 사전에 논리적인 전략을 개발(또는 차용)하고 이를 충실히 실행하는 것으로는 충분하지 않습니다. 질적 연구에서 설계는 지속적인 과정으로, 설계의 다양한 구성 요소들 간에 "앞뒤로 이동(tacking)"하며, 목표, 이론, 연구 질문, 방법, 타당성 위협 등이 서로에 미치는 영향을 평가하는 작업을 포함합니다. 이는 사전에 정해진 시작점에서 출발하거나 고정된 순서에 따라 진행되지 않으며, 설계 구성 요소들 간의 상호 연결성과 상호작용을 포함합니다.

또한 프랭크 로이드 라이트(Frank Lloyd Wright)가 강조했듯, 설계는 그것의 용도뿐만 아니라 환경에도 맞아야 합니다. 연구 과정에서 이 설계가 실제로 어떻게 작동하는지, 환경에 어떤 영향을 주고 받는지 지속적으로 평가하며, 연구가 의도한 목표를 달성할 수 있도록 조정과 변화를 수행해야 합니다.

제가 제시하는 연구 설계 모델은 "상호작용적(interactive)" 모델이라 부릅니다(이와 함께 "체계적(systemic)"이라 부를 수도 있었습니다). 이 모델은 분명한 구조를 가지고 있지만, 동시에 상호 연결되고 유연한 구조입니다. 이 책에서는 연구 설계의 주요 구성 요소를 설명하고, 이러한 구성 요소 간에 일관되고 실행 가능한 관계를 창출하는 전략을 제시합니다. 또한 (7장에서) 설계에서 연구 제안서로 이동하는 명시적인 계획을 제공합니다.

제가 여기에서 제시하는 모델은 다섯 가지 구성 요소로 이루어져 있으며, 각각의 구성 요소가 해결하려는 주요 관심사를 아래에 설명합니다.

Thus, to design a study, particularly a qualitative study, you can’t just develop (or borrow) a logical strategy in advance and then implement it faithfully. Design in qualitative research is an ongoing process that involves “tacking” back and forth between the different components of the design, assessing the implications of goals, theories, research questions, methods, and validity threats for one another. It does not begin from a predetermined starting point or proceed through a fixed sequence of steps, but involves interconnection and interaction among the different design components.

In addition, as Frank Lloyd Wright emphasized, the design of something must fit not only with its use, but also with its environment. You will need to continually assess how this design is actually working during the research, how it influences and is influenced by its environment, and to make adjustments and changes so that your study can accomplish what you want.

My model of research design, which I call an “interactive” model (I could just as well have called it “systemic”), has a definite structure. However, it is an interconnected and flexible structure. In this book, I describe the key components of a research design, and present a strategy for creating coherent and workable relationships among these components. I also provide (in Chapter 7) an explicit plan for moving from your design to a research proposal.

The model I present here has five components, which I characterize below in terms of the concerns that each is intended to address:

- 목표 (Goals)

- 이 연구를 수행할 가치가 있는 이유는 무엇인가요?

- 어떤 문제를 명확히 하고자 하며, 어떤 실천과 정책에 영향을 미치고 싶나요?

- 왜 이 연구를 수행하려고 하며, 그 결과에 대해 우리가 관심을 가져야 하는 이유는 무엇인가요?

- 개념적 틀 (Conceptual Framework)

- 연구하려는 문제, 환경, 또는 사람들에게 어떤 일이 벌어지고 있다고 생각하나요?

- 어떤 이론, 신념, 기존 연구 결과가 연구를 안내하거나 정보를 제공할 것인가요?

- 연구 대상이나 문제를 이해하기 위해 어떤 문헌, 예비 연구, 개인적 경험을 활용할 것인가요?

- 연구 질문 (Research Questions)

- 이 연구를 통해 구체적으로 무엇을 이해하고 싶나요?

- 연구 대상 현상에 대해 무엇을 모르고 있으며, 그것을 배우고자 하는 것은 무엇인가요?

- 연구가 답하려는 질문은 무엇이며, 이러한 질문들은 서로 어떤 관계가 있나요?

- 방법 (Methods)

- 이 연구를 수행하는 과정에서 실제로 무엇을 할 것인가요?

- 데이터를 수집하고 분석하기 위해 어떤 접근 방식과 기술을 사용할 건가요?

- 이 설계 구성 요소는 네 부분으로 나뉩니다:

- (1) 연구 참가자들과 설정한 관계,

- (2) 데이터 수집을 위한 환경, 참가자, 시간과 장소, 그리고 문서와 같은 다른 데이터 출처의 선택(흔히 "표집(sampling)"이라 부름),

- (3) 데이터 수집 방법,

- (4) 데이터 분석 전략 및 기법.

- 타당성 (Validity)

- 연구 결과와 결론이 잘못될 가능성은 무엇인가요?

- 이러한 결과와 결론에 대한 그럴듯한 대안 해석 및 타당성 위협은 무엇이며, 이를 어떻게 다룰 것인가요?

- 당신이 가진 데이터 또는 잠재적으로 수집할 수 있는 데이터가 연구 대상에 대해 가지고 있는 생각을 뒷받침하거나 도전할 수 있는 이유는 무엇인가요?

- 왜 연구 결과를 신뢰해야 할까요?

- Goals

- Why is your study worth doing?

- What issues do you want it to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence?

- Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should we care about the results?

- Conceptual Framework

- What do you think is going on with the issues, settings, or people you plan to study?

- What theories, beliefs, and prior research findings will guide or inform your research, and what literature, preliminary studies, and personal experiences will you draw on for understanding the people or issues you are studying?

- Research Questions

- What, specifically, do you want to understand by doing this study?

- What do you not know about the phenomena you are studying that you want to learn?

- What questions will your research attempt to answer, and how are these questions related to one another?

- Methods

- What will you actually do in conducting this study?

- What approaches and techniques will you use to collect and analyze your data?

- There are four parts of this component of your design:

- (1) the relationships that you establish with the participants in your study;

- (2) your selection of settings, participants, times and places of data collection, and other data sources such as documents (what is often called “sampling”);

- (3) your data collection methods;

- (4) your data analysis strategies and techniques.

- Validity

- How might your results and conclusions be wrong?

- What are the plausible alternative interpretations and validity threats to these, and how will you deal with these?

- How can the data that you have, or that you could potentially collect, support or challenge your ideas about what’s going on?

- Why should we believe your results?

이 구성 요소들은 연구 설계에 대한 많은 다른 논의에서 제시된 것들과 본질적으로 다르지 않습니다(예: LeCompte & Preissle, 1993; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Robson, 2002; Rudestam & Newton, 1992, p. 5). 혁신적인 점은 이러한 구성 요소들 간의 관계를 개념화하는 방식에 있습니다. 이 모델에서는 설계의 다양한 부분들이 선형적 또는 순환적 순서로 연결된 것이 아니라, 통합되고 상호작용하는 전체를 형성하며, 각 구성 요소는 여러 다른 요소와 밀접하게 연결되어 있습니다. 이 다섯 가지 구성 요소 간의 가장 중요한 관계는 그림 1.1에 나타나 있습니다.

여기서 강조한 것 외에도 다른 연결이 있으며, 일부는 점선으로 표시했습니다. 예를 들어, 연구의 목표 중 하나가 참여자들이 그들에게 중요한 문제에 대해 스스로 연구를 수행할 수 있도록 힘을 실어주는 것이라면, 이는 사용하게 될 방법을 형성할 것이며, 반대로 연구에서 실현 가능한 방법은 목표를 제한할 것입니다. 마찬가지로, 연구에서 활용하는 이론과 지적 전통은 가장 중요한 타당성 위협에 대한 관점을 형성하며, 이는 역으로 작용할 수도 있습니다.

이 모델의 상단 삼각형은 긴밀하게 통합된 단위여야 합니다. 연구 질문은 연구의 목표와 명확히 연관되어야 하며, 연구 중인 현상에 대해 이미 알려진 것과 이 현상에 적용할 수 있는 이론적 개념과 모델로부터 영향을 받아야 합니다. 또한, 연구 목표는 현재의 이론과 지식에 의해 영향을 받아야 하며, 어떤 이론과 지식이 관련성이 있는지를 결정하는 것은 목표와 질문에 의존합니다.

마찬가지로, 모델의 하단 삼각형도 긴밀히 통합되어야 합니다. 사용되는 방법은 연구 질문에 답할 수 있어야 하며, 이러한 답변에 대한 타당성 위협을 처리할 수 있어야 합니다. 질문은 또한 방법의 실현 가능성과 특정 타당성 위협의 중요성을 고려하여 구성되어야 하며, 특정 타당성 위협의 개연성과 관련성, 그리고 이를 처리하는 방식은 선택된 질문과 방법에 따라 달라집니다. 연구 질문은 모델의 중심 또는 허브로서 다른 모든 구성 요소를 연결하며, 이 구성 요소들을 정보로 제공하고 이에 민감하게 반응해야 합니다.

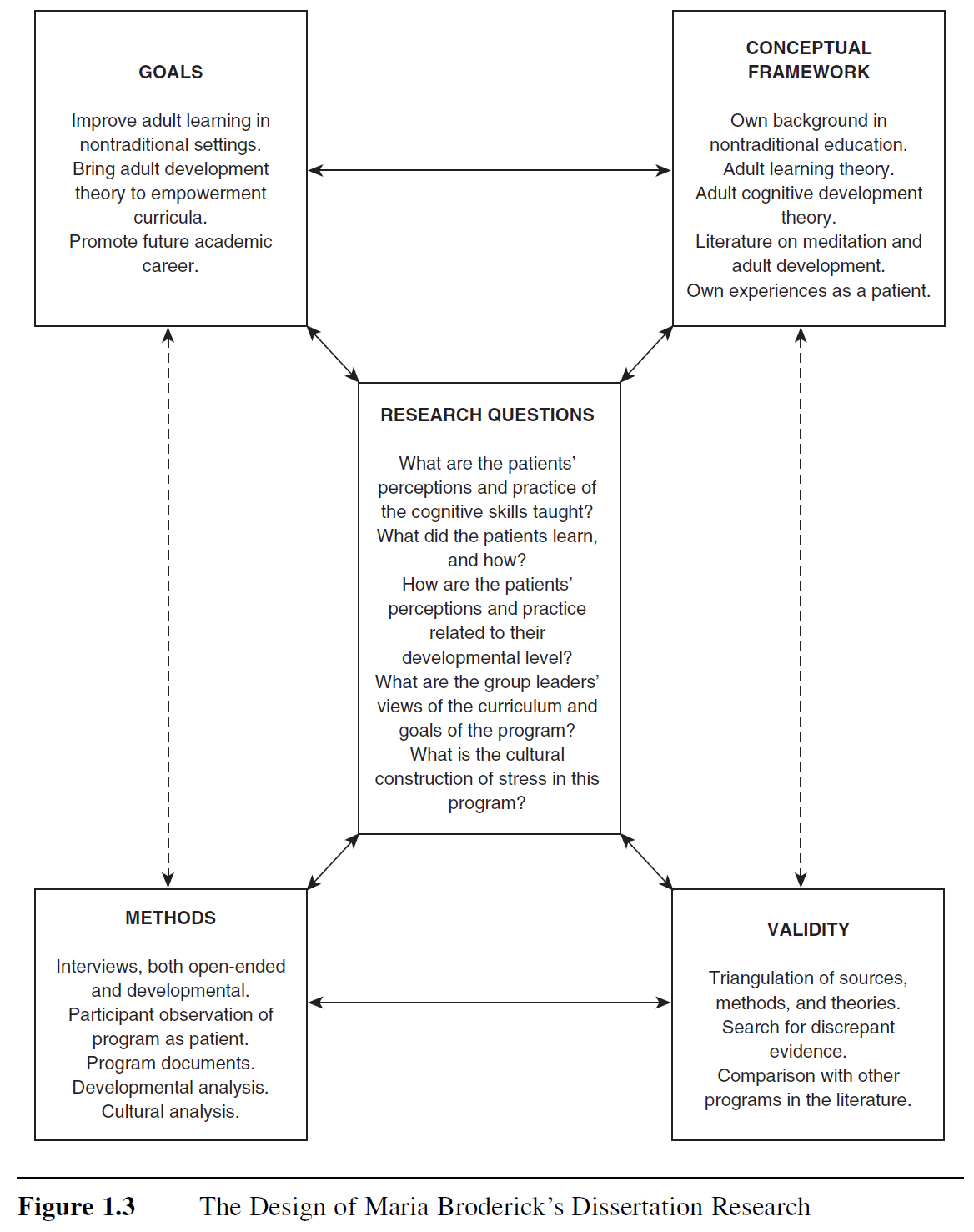

These components are not substantially different from the ones presented in many other discussions of research design (e.g., LeCompte & Preissle, 1993; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Robson, 2002; Rudestam & Newton, 1992, p. 5). What is innovative is the way the relationships among the components are conceptualized. In this model, the different parts of a design form an integrated and interacting whole, with each component closely tied to several others, rather than being linked in a linear or cyclic sequence. The most important relationships among these five components are displayed in Figure 1.1.

There are also connections other than those emphasized here, some of which I have indicated by dashed lines. For example, if a goal of your study is to empower participants to conduct their own research on issues that matter to them, this will shape the methods you use, and, conversely, the methods that are feasible in your study will constrain your goals. Similarly, the theories and intellectual traditions you are drawing on in your research will have implications for what validity threats you see as most important and vice versa.

The upper triangle of this model should be a closely integrated unit. Your research questions should have a clear relationship to the goals of your study, and should be informed by what is already known about the phenomena you are studying and the theoretical concepts and models that can be applied to these phenomena. In addition, the goals of your study should be informed by current theory and knowledge, while your decisions about what theory and knowledge are relevant depend on your goals and questions.

Similarly, the bottom triangle of the model should also be closely integrated. The methods you use must enable you to answer your research questions, and also to deal with plausible validity threats to these answers. The questions, in turn, need to be framed so as to take the feasibility of the methods and the seriousness of particular validity threats into account, while the plausibility and relevance of particular validity threats, and the ways these can be dealt with, depend on the questions and methods chosen. The research questions are the heart, or hub, of the model; they connect all of the other components of the design, and should inform, and be sensitive to, these components.

모델의 다양한 구성 요소 간의 연결은 엄격한 규칙이나 고정된 의미를 가지지 않습니다. 이러한 연결은 설계에서 어느 정도의 "유연함"과 탄력을 허용합니다. 저는 이러한 연결을 "고무줄"로 생각하는 것이 유용하다고 봅니다. 고무줄은 어느 정도까지는 늘어나고 구부러질 수 있지만, 설계의 다른 부분에 명확한 긴장을 가하며, 특정 지점을 넘어서거나 특정 압박을 받게 되면 끊어지게 됩니다. 이 "고무줄" 비유는 질적 설계를 상당히 유연하게 보이게 하지만, 설계의 다른 부분들 간에 서로 제약을 가하며, 이러한 제약이 위반되면 설계가 효과를 잃게 된다는 점을 보여줍니다.

이 다섯 가지 구성 요소 외에도 연구 설계에 영향을 미치는 많은 다른 요소들이 있습니다. 이러한 요소에는 여러분의 자원, 연구 기술, 인식된 문제, 윤리적 기준, 연구 환경, 그리고 수집한 데이터와 데이터로부터 도출한 결과 등이 포함됩니다. 제 견해로는, 이러한 요소들은 연구의 설계에 속하지 않으며, 연구와 설계가 존재하는 환경에 속하거나 연구의 산물에 해당합니다. 배의 설계가 그 배가 만날 바람과 파도의 종류, 그리고 운반할 화물의 종류를 고려해야 하는 것처럼, 이러한 요소들을 연구 설계에 반영해야 합니다. 그림 1.2는 연구 설계와 수행에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 환경적 요소들 중 일부를 보여주며, 이러한 요소들과 연구 설계 구성 요소 간의 주요 연결을 나타냅니다. 이러한 요소와 연결은 이후 장에서 논의될 것입니다.

윤리에 대해 특별히 언급하고 싶은데, 연구 설계의 별도 구성 요소로 윤리를 명시하지 않았기 때문입니다. 이는 윤리가 질적 설계에서 중요하지 않다고 생각해서가 아닙니다. 오히려, 질적 연구에서 윤리적 문제에 대한 관심이 필수적인 것으로 점점 더 인식되고 있기 때문입니다(Christians, 2000; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000; Fine, Weis, Weseen, & Wong, 2000). 대신, 저는 윤리적 고려사항이 설계의 모든 측면에 포함되어야 한다고 믿습니다. 저는 특히 방법론과 관련하여 이러한 윤리적 문제를 다루려고 노력했지만, 이는 연구 목표, 연구 질문의 선택, 타당성 문제, 그리고 개념적 틀에 대한 비판적 평가와도 관련이 있습니다.

The connections among the different components of the model are not rigid rules or fixed implications; they allow for a certain amount of “give” and elasticity in the design. I find it useful to think of them as rubber bands. They can stretch and bend to some extent, but they exert a definite tension on different parts of the design, and beyond a particular point, or under certain stresses, they will break. This “rubber band” metaphor portrays a qualitative design as something with considerable flexibility, but in which there are constraints imposed by the different parts on one another, constraints which, if violated, make the design ineffective.

There are many other factors besides these five components that will influence the design of your study; these include your resources, research skills, perceived problems, ethical standards, the research setting, and the data you collect and results you draw from these data. In my view, these are not part of the design of a study, but either belong to the environment within which the research and its design exist or are products of the research. You will need to take these factors into account in designing your study, just as the design of a ship needs to take into account the kinds of winds and waves the ship will encounter and the sorts of cargo it will carry. Figure 1.2 presents some of the factors in the environment that can influence the design and conduct of a study, and displays some of the key linkages of these factors with components of the research design. These factors and linkages will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

I want to say something specifically about ethics, since I have not identified it as a separate component of research design. This isn’t because I don’t think ethics is important for qualitative design; on the contrary, attention to ethical issues in qualitative research is being increasingly recognized as essential (Christians, 2000; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000; Fine, Weis, Weseen, & Wong, 2000). Instead, it is because I believe that ethical concerns should be involved in every aspect of design. I have particularly tried to address these concerns in relation to methods, but they are also relevant to your goals, the selection of your research questions, validity concerns, and the critical assessment of your conceptual framework.

이 책의 부제가 나타내듯이, 제가 제시하는 설계 접근법은 상호작용적(interactive)입니다. 이는 세 가지 의미에서 상호작용적입니다.

- 첫째, 설계 모델 자체가 상호작용적입니다. 각 구성 요소는 다른 구성 요소에 영향을 미치며, 구성 요소들이 선형적이고 단방향적인 관계로 연결되어 있지 않습니다.

- 둘째, 질적 연구의 설계는 단순히 연구 실천의 고정된 결정 요인이 아니라, 연구가 수행되는 환경에 따라 변화할 수 있어야 합니다. (예제 1.1은 한 연구의 설계 발전 과정에서 이러한 상호작용적 과정을 보여줍니다.)

- 마지막으로, 이 책에 포함된 학습 과정은 상호작용적입니다. 여러분이 자신의 연구 설계를 작업할 수 있게 하는 빈번한 연습 문제들을 포함하고 있습니다. 이 책은 여러분이 암기한 뒤 나중에 연구에 사용할 수 있는 추상적인 연구 설계 원칙만을 제시하지 않습니다. 여러분은 일반화 가능한 원칙을 배우겠지만, 특정 질적 프로젝트의 설계를 만드는 과정을 통해 가장 잘 배울 수 있습니다.

이 설계 모델이 유용한 한 가지 방법은 실제 연구 설계를 개념적으로 매핑하기 위한 도구 또는 템플릿으로 사용하는 것입니다. 이는 설계 과정의 일부로서, 또는 완료된 연구의 설계를 분석하는 데 사용할 수 있습니다. 이 과정은 해당 연구 설계의 특정 구성 요소로 모델의 다섯 구성 요소에 해당하는 원을 채우는 작업을 포함하며, 이를 "설계 지도(design map)"라고 부릅니다. 그림 1.3은 Maria Broderick의 학위 논문 연구의 최종 구조를 나타내는 설계 지도입니다. 다른 설계 지도에 대한 예시는 Maxwell과 Loomis(2002)를 참조하세요.

저는 연구 설계의 유일한 올바른 모델이 있다고 믿지 않습니다. 그러나 제가 제시하는 모델이 두 가지 주요 이유에서 유용한 모델이라고 생각합니다:

- 이 모델은 설계 구성 요소로서 여러분이 결정해야 할 주요 문제들과 연구 제안서에서 다루어야 할 요소들을 명시적으로 식별합니다. 따라서 이러한 구성 요소들이 간과되거나 오해될 가능성이 줄어들며, 체계적으로 다룰 수 있습니다.

- 이 모델은 질적 연구에서 설계 결정의 상호작용적 본성과 설계 구성 요소 간의 다중 연결을 강조합니다. 학위 논문 또는 연구비 지원 제안서가 거절되는 일반적인 이유 중 하나는 설계 구성 요소들 간의 논리적 연결이 명확하지 않기 때문입니다. 제가 제시하는 모델은 이러한 연결을 이해하고 보여주는 것을 더 쉽게 만듭니다.

여러분의 연구에 대한 좋은 설계는 마치 배의 좋은 설계처럼 연구를 안전하고 효율적으로 목표 지점에 도달하게 도와줄 것입니다. 반면, 구성 요소들이 잘 통합되지 않았거나 호환되지 않는 나쁜 설계는 기껏해야 비효율적이며, 최악의 경우 목표를 달성하지 못할 것입니다.

As the subtitle of this book indicates, my approach to design is an interactive one. It is interactive in three senses. First, the design model itself is interactive; each of the components has implications for the other components, rather than the components being in a linear, one-directional relationship with one another. Second, the design of a qualitative study should be able to change in response to the circumstances under which the study is being conducted, rather than simply being a fixed determinant of research practice. (Example 1.1 illustrates both of these interactive processes in the evolution of the design of one study.) Finally, the learning process embodied in this book is interactive, with frequent exercises that enable you to work on the design of your own study. This book does not simply present abstract research design principles that you can memorize and then later use in your research. You will learn generalizable principles, but you’ll learn these best by creating a design for a particular qualitative project.

One way in which the design model presented here can be useful is as a tool or template for conceptually mapping the design of an actual study, either as part of the design process or in analyzing the design of a completed study. This involves filling in the circles for the five components of the model with the specific components of that study’s design, a strategy that I call a “design map.” Figure 1.3 is a design map of the eventual structure of Maria Broderick’s dissertation research; see Maxwell and Loomis (2002) for other such maps.

I do not believe that there is one right model of, or for, research design. However, I think that the model that I present here is a useful model for two main reasons:

- It explicitly identifies as components of design the key issues about which you will need to make decisions and which will need to be addressed in your research proposal. These components are therefore less likely to be overlooked or misunderstood, and can be dealt with in a systematic manner.

- It emphasizes the interactive nature of design decisions in qualitative research and the multiple connections among design components. A common reason that dissertation or funding proposals are rejected is because they do not make clear the logical connections among the design components, and the model I present here makes it easier to understand and demonstrate these connections.

A good design for your study, like a good design for a ship, will help it to safely and efficiently reach its destination. A poor design, one in which the components are not well integrated or are incompatible, will at best be inefficient, and at worst will fail to achieve its goals.

이 책의 구성

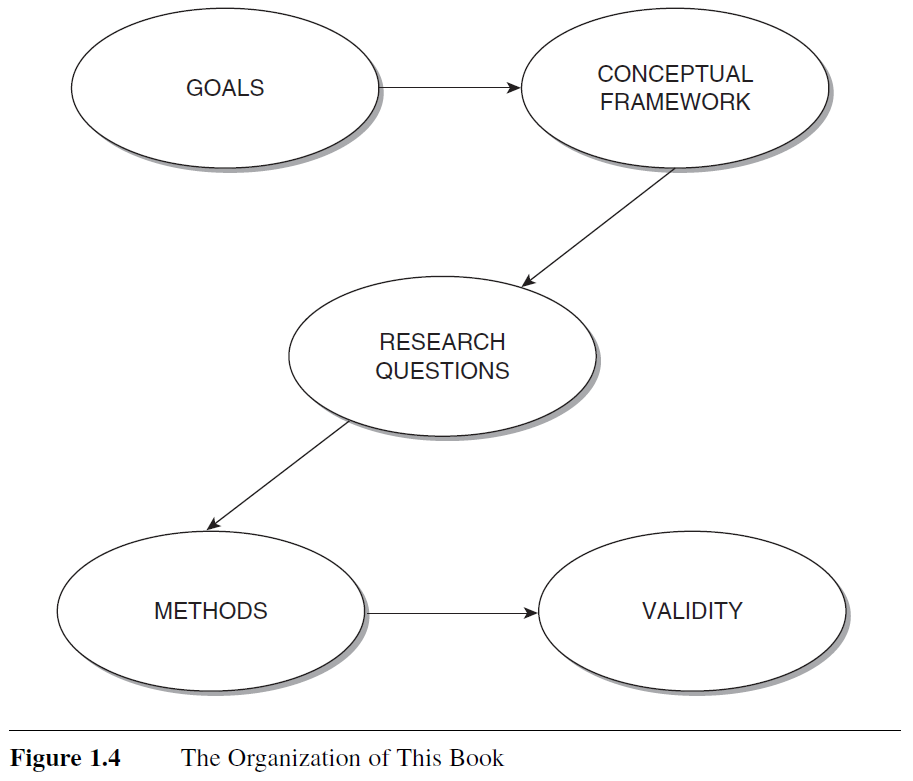

이 책은 질적 연구를 설계하는 과정을 안내하도록 구성되었습니다. 설계 결정을 내려야 하는 주요 문제들을 강조하며, 이러한 결정에 정보를 제공해야 할 고려 사항들을 제시합니다. 책의 각 장은 설계의 한 구성 요소를 다루며, 이러한 장들은 논리적 순서를 형성합니다. 그러나 이 조직 방식은 개념적이고 설명을 위한 장치일 뿐, 실제 연구를 설계할 때 따라야 할 절차는 아닙니다. 각 구성 요소에 대한 결정을 내릴 때, 다른 모든 구성 요소에 대한 생각을 고려해야 하며, 새로운 정보나 생각의 변화에 따라 이전 설계 결정을 수정해야 할 수도 있습니다.

이 책은 이 모델의 구성 요소를 따라 Z자 형태(Figure 1.4)로 진행합니다. 목표(Chapter 2)로 시작하는 이유는 목표가 중요할 뿐만 아니라 기본적이기 때문입니다. 연구를 수행하는 이유가 명확하지 않으면 설계의 다른 부분에 대한 결정을 내리기가 어려울 수 있습니다. 다음으로 논의되는 것은 개념적 틀(Chapter 3)로, 이는 목표와 밀접하게 연결되어야 하며, 목표와 틀이 함께 연구 질문을 형성하는 데 큰 영향을 미칩니다. 따라서 연구 질문(Chapter 4)은 논리적으로 다음 주제가 됩니다. 이 세 가지 구성 요소는 일관된 단위를 형성해야 합니다.

다음으로 논의되는 구성 요소는 방법론(Chapter 5)입니다. 데이터를 실제로 수집하고 분석하여 연구 질문에 답하는 방식입니다. 그러나 이러한 방법과 분석은 타당성 문제(Chapter 6)와 연결되어야 합니다. 즉, 무엇이 잘못될 수 있는지, 대안적인 가능한 답변보다 더 신뢰할 수 있는 답변이 되려면 무엇이 필요한지를 고려해야 합니다. 연구 질문, 방법, 타당성은 또한 통합된 단위를 형성해야 하며, 질문에 대한 답을 얻기 위한 방법과 가능한 타당성 위협에 직면하여 잠재적 답변의 신뢰성을 보장하기 위한 수단이 명확히 개념화되고 연구 질문과 연결되어야 합니다.

마지막으로, Chapter 7에서는 설계 모델이 연구 제안서 개발에 미치는 영향을 논의하고, 설계에서 제안서로 나아가는 방법과 가이드라인을 제공합니다.

THE ORGANIZATION OF THIS BOOK

This book is structured to guide you through the process of designing a qualitative study. It highlights the issues for which design decisions must be made, and presents some of the considerations that should inform these decisions. Each chapter in the book deals with one component of design, and these chapters form a logical sequence. However, this organization is only a conceptual and presentational device, not a procedure to follow in designing an actual study. You should make decisions about each component in light of your thinking about all of the other components, and you may need to modify previous design decisions in response to new information or changes in your thinking.

This book takes a Z-shaped path (Figure 1.4) through the components of this model, beginning with goals (Chapter 2). The goals of your study are not only important, but also primary; if your reasons for doing the study aren’t clear, it can be difficult to make any decisions about the rest of the design. Your conceptual framework (Chapter 3) is discussed next, both because it should connect closely to your goals and because the goals and framework jointly have a major influence on the formulation of research questions for the study. Your research questions (Chapter 4) are thus a logical next topic; these three components should form a coherent unit.

The next component discussed is methods (Chapter 5): how you will actually collect and analyze the data to answer your research questions. However, these methods and analyses need to be connected to issues of validity (Chapter 6): how you might be wrong, and what would make your answers more believable than alternative possible answers. Research questions, methods, and validity also should form an integrated unit, one in which the methods for obtaining answers to the questions, and the means for assuring the credibility of the potential answers in the face of plausible validity threats, are clearly conceptualized and linked to the research questions.

Finally, Chapter 7 discusses the implications of my model of design for developing research proposals, and provides a map and guidelines for how to get from one to the other.

이 책의 연습 문제

C. Wright Mills는 다음과 같이 썼습니다:

사회과학자들에게 발생하는 최악의 일 중 하나는 특정 연구나 “프로젝트”에 대해 자금을 요청해야 할 때 단 한 번만 자신의 “계획”을 작성할 필요성을 느끼는 것입니다. 대부분의 계획은 자금을 요청하기 위해 이루어지며, 또는 적어도 신중히 작성됩니다. 그러나 이러한 관행이 얼마나 표준적이든 간에, 저는 이것이 매우 나쁜 일이라고 생각합니다. 이는 어느 정도는 판매 기술이 될 수밖에 없으며, 현재의 기대를 감안할 때 고심 끝에 위선을 초래할 가능성이 높습니다. 프로젝트는 마땅히 해야 할 시점보다 훨씬 이전에 어떤 방식으로든 “발표”되고, 완성된 형태로 조작되기 쉽습니다. 그것이 제시된 연구뿐만 아니라, 다른 목적으로 자금을 얻기 위해 만들어진 경우가 많습니다. 사회과학자로 활동하는 사람은 주기적으로 “나의 문제와 계획의 상태”를 검토해야 합니다. (Mills, 1959, p. 197)

그는 각 연구자가 자신의 연구에 대해 “자신을 위해, 그리고 아마도 친구들과의 논의를 위해” 정기적이고 체계적으로 글을 써야 한다고 열렬히 주장했고(p. 198), 이러한 글을 파일로 보관해야 한다고 했습니다. 질적 연구자들은 이를 보통 “메모(memos)”라고 부릅니다.

이 책의 모든 연습 문제는 일종의 메모이며, 메모의 본질과 이를 효과적으로 사용하는 방법에 대해 간략히 논의하고자 합니다. 메모(때로는 “분석 메모”라고도 불림)는 여러 가지 목적으로 사용할 수 있는 매우 다재다능한 도구입니다. 이 용어는 실제 필드 노트, 전사(transcription), 또는 코딩 외에 연구와 관련하여 연구자가 작성하는 모든 글을 의미합니다. 메모는 전사에 대한 간단한 여백 주석, 필드 저널에 기록된 이론적 아이디어에서부터 완전한 분석 에세이에 이르기까지 다양할 수 있습니다. 이 모든 메모의 공통점은 아이디어를 종이에(또는 컴퓨터에) 기록하고, 이를 반성과 분석적 통찰을 촉진하는 도구로 사용하는 방법이라는 점입니다.

메모에 자신의 생각을 기록하면 필드 노트와 인터뷰 전사처럼 코딩하고 파일로 저장할 수 있으며, 나중에 이를 다시 참조하여 아이디어를 발전시킬 수 있습니다. 메모를 작성하지 않는 것은 연구에서 알츠하이머병을 앓는 것과 같습니다. 필요할 때 중요한 통찰을 기억하지 못할 수 있기 때문입니다. Peters(1992, p. 123)는 Lewis Carroll의 Through the Looking Glass에서 메모의 이러한 기능에 대해 인용했습니다:

“그 순간의 공포를,” 왕이 계속 말했다, “나는 절대, 절대 잊지 않을 것이다.”

“그러나 잊을 거예요,” 여왕이 말했다, “기록하지 않으면.”

THE EXERCISES IN THIS BOOK

C. Wright Mills wrote that:

One of the very worst things that happens to social scientists is that they feel the need to write of their “plans” on only one occasion: when they are going to ask for money for a specific piece of work or “a project.” It is as a request for funds that most planning is done, or at least carefully written about. However standard the practice, I think this very bad: it is bound in some degree to be salesmanship, and, given prevailing expectations, very likely to result in painstaking pretensions; the project is likely to be “presented,” rounded out in some manner long before it ought to be; it is often a contrived thing, aimed at getting the money for ulterior purposes, however valuable, as well as for the research presented. A practicing social scientist ought periodically to review “the state of my problems and plans.” (Mills, 1959, p. 197)

He went on to make an eloquent plea that each researcher write regularly and systematically about his or her research, “just for himself and perhaps for discussion with friends” (p. 198), and to keep a file of these writings, which qualitative researchers usually call “memos.”

All of the exercises in this book are memos of one sort or another, and I want to briefly discuss the nature of memos and how to use them effectively. Memos (sometimes called “analytic memos”) are an extremely versatile tool that can be used for many different purposes. This term refers to any writing that a researcher does in relationship to the research other than actual field notes, transcription, or coding. A memo can range from a brief marginal comment on a transcript or a theoretical idea recorded in a field journal to a full-fledged analytic essay. What all of these have in common is that they are ways of getting ideas down on paper (or in a computer), and of using this writing as a way to facilitate reflection and analytic insight.

When your thoughts are recorded in memos, you can code and file them just as you do your field notes and interview transcripts, and return to them to develop the ideas further. Not writing memos is the research equivalent of having Alzheimer’s disease; you may not remember your important insights when you need them. Peters (1992, p. 123) cited Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass on this function of memos:

“The horror of that moment,” the King went on, “I shall never, never forget.”

“You will, though,” said the Queen, “unless you make a memorandum of it.”

이 책에서 사용된 많은 예시들은 메모이거나 메모를 기반으로 합니다. 메모는 여러분이 자신의 아이디어를 발전시키기 위해 사용할 수 있는 가장 중요한 기법 중 하나입니다. 따라서 메모를 단순히 이미 도달한 이해를 기록하거나 제시하는 방식으로만 생각하지 말고, 주제, 환경, 또는 연구를 이해하는 데 도움을 주는 도구로 생각해야 합니다. 메모는 여러분의 독서와 아이디어, 그리고 현장 연구에 대한 성찰을 포함해야 합니다. 메모는 방법론적 문제, 윤리적 문제, 개인적인 반응 또는 그 외의 어떤 주제에 대해서도 작성할 수 있습니다. 저는 이 책을 쓰고 수정하는 동안 연구 설계에 대한 수많은 메모를 작성했습니다.

메모는 주제, 환경, 연구 또는 데이터를 이해하는 데 직면한 문제를 해결하기 위한 방법으로 작성하세요. 발전시키고 싶은 아이디어가 떠오르거나 단순히 나중에 발전시키기 위해 아이디어를 기록하려 할 때 메모를 작성하세요. 연구 프로젝트 전반에 걸쳐 많은 메모를 작성하세요. 질적 연구에서는 설계가 연구 시작 단계에만 이루어지는 것이 아니라, 연구 전체 과정에서 계속 진행된다는 점을 기억하세요. 메모를 일종의 분산된 필드 저널로 생각하세요. 선호한다면 실제 저널에 메모를 작성할 수도 있습니다.

메모가 어떤 형태로 작성되든, 그 가치는 두 가지에 달려 있습니다.

- 첫째, 단순히 사건과 생각을 기계적으로 기록하는 것이 아니라, 진지한 성찰, 분석, 자기비판에 참여하는 것입니다.

- 둘째, 메모를 체계적이고 검색 가능한 방식으로 조직하여, 관찰과 통찰을 쉽게 찾아보고 나중에 검토할 수 있게 하는 것입니다.

저의 경우 메모 작성은 주로 두 가지 형태로 이루어집니다. 하나는 항상 가지고 다니는 3×5 카드에 아이디어를 적어 날짜와 주제로 색인을 만드는 것이고, 다른 하나는 특정 프로젝트와 관련된 컴퓨터 파일에 작성하는 긴 메모입니다. 캐나다 북부 이누이트 공동체에서 박사 논문 연구를 수행하는 동안, 저는 필드 저널도 작성했는데, 이는 연구 상황에 대한 개인적인 반응을 이해하는 데 매우 유용했습니다. 또한 동료 연구자나 학생들과 메모를 공유하고 피드백을 받는 것도 매우 유용할 수 있습니다.

메모는 주로 사고를 위한 도구이지만, 이후 제안서, 보고서, 또는 출판물에 포함될 자료의 초기 초안으로도 사용할 수 있습니다(대개 상당한 수정과 함께). 이 책의 메모 연습 문제 대부분을 이러한 방식으로 사용할 수 있도록 설계하려고 노력했습니다. 그러나 메모를 다른 사람과 소통하는 수단으로 주로 생각하면, 메모를 가장 유용하게 만드는 데 필요한 반성적 글쓰기에 방해가 될 수 있습니다. 특히, Becker(1986)가 말한 "세련된 글쓰기"—즉, 다른 사람들에게 깊은 인상을 주려는 과장되고 장황한 언어—를 주의하세요. 작문 강사들 사이에서 자주 인용되는 말은 “글을 쓸 때, 뇌에 턱시도를 입히지 마라”(Metzger, 1993)입니다.

Many of the examples used in this book are memos, or are based on memos. Memos are one of the most important techniques you have for developing your own ideas. You should therefore think of memos as a way to help you understand your topic, setting, or study, not just as a way of recording or presenting an understanding you’ve already reached. Memos should include reflections on your reading and ideas as well as your fieldwork. Memos can be written on methodological issues, ethics, personal reactions, or anything else; I wrote numerous memos about research design during the writing and revising of this book.

Write memos as a way of working on a problem you encounter in making sense of your topic, setting, study, or data. Write memos whenever you have an idea that you want to develop further, or simply to record the idea for later development. Write lots of memos throughout the course of your research project; remember that in qualitative research, design is something that goes on during the entire study, not just at the beginning. Think of memos as a kind of decentralized field journal; if you prefer, you can write your memos in an actual journal.

Whatever form these memos take, their value depends on two things. The first is that you engage in serious reflection, analysis, and self-critique, rather than just mechanically recording events and thoughts. The second is that you organize your memos in a systematic, retrievable form, so that the observations and insights can easily be accessed for future examination. I do my own memo writing primarily in two forms: on 3 × 5 cards, which I always carry with me for jotting down ideas and which I index by date and topic, and in computer files relating to particular projects, which I use for longer memos. During my dissertation research in an Inuit community in northern Canada, I also kept a field journal, which was invaluable in making sense of my personal responses to the research situation. It can also be very useful to share some of your memos with colleagues or fellow students for their feedback.

Although memos are primarily a tool for thinking, they can also serve as an initial draft of material that you will later incorporate (usually with substantial revision) in a proposal, report, or publication, and I’ve tried to design most of the memo exercises in this book so that they can be used in this way. However, thinking of memos primarily as a way of communicating to other people will usually interfere with the kind of reflective writing that you need to do to make memos most useful to you. In particular, beware of what Becker (1986) called “classy writing”—pretentious and verbose language that is intended to impress others rather than to clarify your ideas. A saying among writing instructors is, “When you write, don’t put a tuxedo on your brain” (Metzger, 1993).

'Wilson Centre' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [Cartographies of Knowledge] Ch 1. INTRODUCTION (0) | 2025.01.08 |

|---|---|

| [The foundations of social research] Ch 1. Introduction: the research process (0) | 2025.01.08 |

| Carla Willig’s model of Foucauldian Discourse Analysis (feat. ChatGPT) (5) | 2024.12.19 |

| [질적연구] 목적적 샘플링(PURPOSEFUL SAMPLING) (5) | 2024.10.31 |

| [리더십과 EDI] 코로나19 기간 중 형평성을 갖춘 의사 학자들의 학업 생산성: 스코핑 리뷰 (5) | 2024.10.25 |