이 책은 진리, 객관성, 지식에 대한 오랜 가정들을 의문에 부치는 지적 모험으로 시작됩니다. 이러한 사회 구성주의적 사상으로의 모험은 지식의 여러 학문을 휩쓸며 논란을 일으키고, 탐구를 자극하며, 계속되는 창조적 파동을 촉발했습니다. 그러나 이 모험이 전개됨에 따라 초점은 행동의 세계로 이동합니다. 이 지적 소용돌이는 우리의 삶의 세계로 스며들어, 우리의 삶의 방식에 대한 중요한 질문을 제기하고, 동시에 교육, 평화 구축, 치료와 건강관리, 조직 개발 등 다양한 분야에서 혁신적인 실천들을 영감으로 제공합니다. 하지만 궁극적으로 이 책은 우리가 세상에서 함께 살아가는 능력에 관한 것입니다. 우리는 역사적으로 그 어느 때보다도 서로 마주하며, 상호 이해, 소외, 억압, 갈등과 같은 문제에 직면하고 있습니다. 조화와 공공의 복지를 달성할 수 있는 우리의 능력은 심각한 의문에 처해 있습니다. 이제 우리는 행성의 생존이 이러한 관계의 격동 속에서 항해할 수 있는 우리의 능력에 달려 있음을 깨닫고 있습니다.

이 첫 번째 장에서는 우리가 무엇이 진리이고 가치 있는지에 대한 끝없는 다양성의 주장 속에서 살아가는 도전에 대해 간략히 살펴봅니다. 이는 사회 구성주의의 중심 아이디어를 예비적으로 그리는 데에 길을 마련할 것입니다. 구성주의적 아이디어는 미래의 조화를 위한 경로를 제공하지는 않지만, 그 경로를 만드는 데 중요한 자원입니다. 이러한 넓은 윤곽을 이해한 후, 우리는 학문적 세계를 불태운 세 가지 지적 흐름을 탐구합니다. 이들은 동시에 사회 구성주의 이론과 실천이 성장한 지적 토양으로 기능합니다. 마지막으로, 구성주의 아이디어가 함께 살아가는 세계화를 위한 변화를 위한 자원으로서 가지는 잠재력을 엿봅니다.

This book begins with an intellectual adventure, one that places time-honoured assumptions about truth, objectivity, and knowledge in question. This adventure into social constructionist ideas has swept across the disciplines of knowledge, provoking controversy, sparking inquiry, and unleashing continuing waves of creativity. Yet, as the adventure unfolds, the focus shifts to the world of action. The intellectual whirlwind finds its way into our life-worlds – posing significant questions about our ways of life, and simultaneously inspiring an array of innovative practices – in education, peacebuilding, therapy and healthcare, organizational development and more. In the end, however, this is a book about our ability to live together in the world. We have reached a point in history at which we, the peoples of the world, are confronting each other as never before. Challenges of mutual understanding, alienation, oppression and conflict are paramount. Our capacities to achieve harmony and common wellbeing are in serious question. As we realize, planetary survival now depends on our capacities to navigate these roiling waters of relating.

In this opening chapter we first take a brief look at the challenge of living in a world of unending variation in our claims to what is true and valuable. This will prepare the way for a preliminary sketch of central ideas in social construction. While constructionist ideas do not offer the path to future harmony, they are invaluable resources for creating that path. With these broad strokes in hand, we then explore three intellectual currents that have set the academic world on fire. They simultaneously serve as the intellectual seedbed from which social constructionist theory and practice have grown. Finally, we glimpse some of the potentials of constructionist ideas as resources for a globalized transformation in living together.

단어와 세계

제가 여러분과 거의 알려지지 않은 비밀을 하나 공유하며 시작해보겠습니다: 저는 날 수 있습니다! 정말입니다. 믿기 힘들겠지만, 저는 실제로 날 수 있습니다. 아마 여러분은 제가 농담을 하고 있다고 생각하며 미소를 지을지도 모릅니다. 아니요, 저는 이 문제에 대해 매우 진지합니다. 그리고 대부분의 사람들도 제가 정신적으로 문제가 있거나 거짓말을 하고 있다고는 말하지 않을 것입니다. ‘좋아요,’ 여러분은 이렇게 답할 수도 있겠죠. ‘그럼 날아보세요!’ 이 시점에서 저는 의자에서 일어나 15cm 정도 공중으로 점프합니다. ‘그건 나는 게 아니잖아요!’ 여러분은 말할 것입니다. ‘그건 단지 점프일 뿐이에요!’ 하지만 사실, 그것이 제가 나는 것이라고 부르는 것입니다. 그렇다면, 저와 여러분 중 누가 제가 날 수 있는지에 대해 정확히 보고하고 있는 걸까요?

물론 대부분의 영어 사용자는 제가 한 행동을 날기보다는 점프라고 부를 것입니다. 하지만 만약 제가 저와 같은 의견을 가진 친구들을 가지고 있다면 어떻게 될까요? ‘그래, Gergen은 날 수 있어. 방금 보여줬잖아.’ 이 시점에서, 제가 날 수 있다는 진실은 단순히 숫자의 문제가 됩니다. 그리고 만약 숫자의 문제라면, 제가 날 수 있다고 선언하려면 몇 명의 사람들이 제 편에 있어야 할까요? 제가 소셜 미디어에서 팔로워를 늘리고 광고 캠페인을 시작한다면 어떨까요? 만약 여러분이 제 능력을 인정하지 않는 이상하고 웃기는 소수파가 된다면 어떻게 될까요? 이 문제의 진실은 단순히 사회적 합의에만 달려 있을까요?

이것은 사소한 문제가 아닙니다. 과학의 목표가 세상에 대한 진실을 밝히는 것이 아닌가요? 배심원 재판은 사실에 근거해 유죄나 무죄를 판단하려고 하지 않나요? 우리는 신문이 우리에게 ‘실제로 벌어지고 있는 일’을 말해주기를 원하지 않나요? 우리는 현실과 동떨어져 있다고 여겨지는 사람들을 제도적으로 격리하지 않나요? 이 모든 경우에서 진실은 단순히 사회적 합의의 문제일까요? 이러한 문제들은 생사와도 관련될 수 있습니다. 물론, 여러분은 제가 과장하고 있다고 말할지도 모릅니다. 제 나는 사례에 대해, 여러분은 단순히 우리가 같은 것을 두고 다른 단어를 사용하고 있다고 결론지을 수도 있습니다. 하지만 이제 다음과 같은 진술들을 고려해 보세요:

- 인간은 자유의지를 가지고 있다.

- 두 가지 성별, 즉 남성과 여성이 존재한다.

- 임산부가 가진 수정란은 인간이다.

- 세계 인구는 여섯 가지 기본 인종으로 구성되어 있다.

- 인간은 물고기에서 진화했다.

- 지구는 거대한 거북이 등에 서 있는 네 마리의 코끼리에 의해 지탱되고 있다.

WORDS AND WORLDS

Let me begin by sharing with you a little-known secret: I can fly! Truly, while it may seem unbelievable, I can actually fly. Perhaps you are smiling, knowing that I must be joking. No, I am quite sincere in this matter, nor would most people say that I am either mentally ill or a liar. ‘OK,’ you might reply, ‘let me see you fly!’ At this point I rise from my chair and leap 6 inches into the air. ‘That’s not flying!’ you announce, ‘That’s just a jump!’ But in fact, that is what I myself call flying. Which of us, then, is reporting accurately on whether I can fly? Of course, most English speakers would agree with you that my action is a jump, not flying. But what if I had a close group of friends who would agree with me? ‘Yes, Gergen can fly. He just showed you.’ At this point, the truth of my ability to fly is just a matter of numbers. And if a matter of numbers, then how many people do I need on my side before I can declare the truth of my flying abilities? What if I built a following on social media, and put on an ad campaign? What if you became a weird and laughable minority not acknowledging my abilities? Does ‘the truth of the matter’ rest solely on social agreement?

This is not a trivial issue. Isn’t the aim of science to reveal the truth about the world? Don’t jury trials seek to determine guilt or innocence on the basis of the facts? Don’t we want newspapers to tell us about what is ‘really going on’? Don’t we institutionalize people because they are ‘out of touch with reality’? Is truth in all these cases just a question of social agreement? These can be issues of life and death. Of course, you might say that I am over-stating the case. In the case of my flying, you might conclude that our conflict simply rests on our using different words for the same thing. But now consider the following statements about what is the case:

- Human beings have free will.

- There are two genders: masculine and feminine.

- The fertilized egg carried by a pregnant woman is a human being.

- The world’s population is composed of six basic races.

- Humans descended from fish.

- The Earth is supported by four elephants standing on the back of a turtle.

이것들은 많은 사람들이 동의하지만, 동시에 많은 사람들이 동의하지 않는 진술들입니다. 또한, ‘우리는 단지 다른 단어를 사용하고 있을 뿐이다’라고 말함으로써 쉽게 결론지을 수 있는 문제도 아닙니다. 이러한 경우들 중 일부에서는 단어 선택이 생사의 문제로 직결되기도 합니다. 자유의지의 경우, 어떤 사람의 행동이 ‘자유롭게 선택된’(의도적인) 것으로 간주되느냐, 아니면 ‘뇌 상태에 의해 결정된’ 것으로 간주되느냐에 따라 평생 감옥에 갇힐 수도 있습니다. 임산부의 수정란이 인간인지의 여부는 많은 사람들에게 dos literal한 생사의 문제입니다. 동의하는 사람들은 낙태를 살인의 한 형태로 보게 될 것입니다. 단어의 선택이 선과 악 사이의 선택이 되는 것입니다.

더 나아가, 이러한 사례들 중 일부에서는 사람들이 같은 것을 묘사하는 데 다른 단어를 사용하고 있다고 말하는 것이 불가능합니다. 제가 날 수 있다는 예와는 달리, 우리는 의도를 관찰하거나, 배아가 인간이 되는 지점을 관찰하거나, 네 마리의 코끼리와 거북이를 관찰할 수 없습니다. 또한, 우리는 동기, 정의, 희망, 영감, 신(God) 등 수천 가지 용어를 관찰할 수 없으며, 이러한 용어들은 많은 사람들이 존재한다고 믿는 것에 정보를 제공합니다. 더욱이, 어떤 사람들은 단순히 단어를 사용하는 것만으로도 학대를 받을 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 인종의 수나 남성과 여성 여부에 대한 질문을 제기하는 것만으로도 많은 사람들에게 억압적일 수 있습니다.

지금 세계의 사람들은 그 어느 때보다도 더 가까이 모이고 있습니다. 디지털 통신 기술은 즉각적이고 끊임없는 소통을 가능하게 합니다. 대중교통, 항공 여행, 인간 이주는 역사상 최고조에 달했습니다. 카메룬 철학자 아실 음벰베(Achille Mbembe)의 말을 빌리자면, 우리는 ‘행성적 얽힘의 시대’에 살고 있습니다. 이는 또한 우리의 의미 세계가 충돌하는 시대이기도 합니다. 현재 세계에는 6,000개 이상의 활성 언어가 존재하며, 이는 세상을 묘사하고, 설명하며, 돌보는 방법들입니다. 심지어 같은 언어 공동체 내에서도 엄청난 차이가 존재할 수 있습니다. 정치 체제, 종교, 민족적 전통, 공동체, 가족, 혹은 부부 관계에 따라 현재의 합의를 방해할 수 있는 잠재력이 늘 도사리고 있습니다. 기독교 교회만 보더라도 약 45,000개의 종파가 존재하며, 각각은 자신들만의 독특한 주장과 그 주장에 부여하는 가치를 가지고 있습니다. 우리는 이러한 차이들이 완전히 해소되고, 공감적 이해가 완전히 이루어지는 시간을 희망해야 할까요? 그러나 이마저도 저항이 있을 것입니다. 많은 사람들에게 그러한 보편적 합의는 억압적이고 위험하게 마비되는 것으로 간주될 수 있습니다.

또한, 현재의 논쟁을 풀어내는 것이 핵심 문제가 아닙니다. 새로운 합의의 영역이 끊임없이 형성되고 있으며, 이로 인해 현재의 합의에 대한 새로운 도전이 발생합니다. 인터넷 통신은 아무리 사소한 판타지, 취향, 목표라 하더라도 비슷한 생각을 가진 사람들을 연결할 수 있습니다. 우리가 계속해서 다양성의 다중 우주(pluriverse) 속에서 살고 있다면, 우리는 어떻게 생존해야 할까요?

These are statements about which many agree, but many do not. Nor can we easily settle the case by saying, ‘Well, we are just using different words.’ In some of these cases it is a matter of life and death as to the particular choice of words. In the case of free will, one may be imprisoned for life depending on whether their actions are called ‘freely chosen’ (intentional), as opposed to ‘determined by a brain condition’. For many people, the question of whether the fertilized egg is a human being is literally a matter of life or death. Those who agree will also see abortion as a form of murder. The choice of words has become a choice between good and evil.

To press further, it’s impossible in some of these cases to say that people are indeed using different words to describe the same thing. Unlike the example of my flying, we can’t observe an intention, the point at which an embryo becomes a human being, or the four elephants and the turtle. Nor can we observe motivation, justice, hope, inspiration, God, and thousands of other terms that inform so many of us about what exists. Still further, there are many who would suffer abuse by simply using the word as if it did refer to the world. Simply posing the question about the number of races, or whether one is male or female is oppressive to many.

The peoples of the world now come together as never before. Technologies of digital communication allow instantaneous, non-stop communication. Mass transportation, air travel, and human migration are at an all-time high. In the words of Cameroon philosopher Achille Mbembe, we live in ‘an age of planetary entanglement’. It is also a confrontation in our worlds of meaning. There are currently more than 6,000 active languages in the world, ways of describing, explaining, and caring. Even within a language community there can be enormous differences. Regardless of the political system, religion, ethnic tradition, community, family, or couple, the potential for disruptive disagreement is ever at hand. Within the Christian church alone, there are some 45,000 denominations, each of which differs from all others in its claims to what is the case and the value placed on these claims. Should we hope that for an ultimate untangling of these differences, a time when full and empathic understanding will emerge? Even here, there would be resistance. For many, such universal accord would be found both stifling and dangerously paralysing.

Nor is it a question of untangling the current disagreements, as new enclaves of agreement are ever forming, and thus new challenges to current agreements. Internet communication allows any small movement – no matter how marginal the fantasy, the taste, or the goal – to locate the like-minded. If we live in an ever-emerging pluriverse of differences, how are we to survive?

의미 형성에 초점 맞추기

무엇이 현실이고, 진실이며, 합리적이고, 옳은지에 대한 상충되는 견해들은 끝이 없을 수 있습니다. 중요한 문제는 이러한 차이가 우리가 이 행성에서 함께 살아갈 수 있는 능력을 저해하지 않도록 하는 방법은 무엇인가 하는 점입니다. 혹은 더 긍정적으로, 그러한 차이들이 어떻게 행성의 안녕에 기여할 수 있을까요? 이러한 어려운 질문들에 대한 하나의 답은 이러한 차이 그 자체에서 벗어나 그것들이 어떻게 만들어졌는지의 과정에 초점을 맞추는 데서 시작됩니다. 예를 들어, 내가 날 수 있는지, 혹은 자유의지가 있는지에 대해 논의하는 것에서 벗어나, 이러한 아이디어들이 처음에 어떻게 만들어졌는지에 주목하는 것입니다. 여기에서 사회 구성의 드라마가 시작됩니다. 즉, 우리가 진실, 합리성, 선이라고 여기는 것의 기원, 한계, 그리고 가능성에 대한 초점의 이동이 이루어집니다. 여기에서 우리는 의미의 바다를 넘어, 의미를 만들어내는 과정 자체를 탐구하게 됩니다.

철학자 넬슨 굿맨(Nelson Goodman)이 한때 물었던 것처럼, “내가 세상에 대해 묻는다면, 당신은 하나 이상의 관점에서 그것이 어떤지 말해줄 수 있습니다. 그러나 내가 모든 관점에서 벗어난 상태에서 그것이 어떤지 말해달라고 강요한다면, 당신은 무엇을 말할 수 있겠습니까?” 결국, 세상에 대한 모든 설명은 어떤 배경이나 관점에서 비롯된 것이며, 여기에서 우리는 우리의 이해의 기반과 그것들의 경계를 완화하는 수단을 찾을 수 있습니다. 실제로, 현실과 가치가 형성되는 방식을 중심에 두면, 현실과 선에 대한 새로운 그리고 더 희망적인 비전을 형성할 길이 열립니다. 차이는 갈등을 요구하지 않으며, 주의를 기울이면 안녕의 차원을 확장하는 삶의 형태를 낳을 수 있습니다.

MEANING MAKING IN FOCUS

Competing views of what is real, true, rational or right may be interminable. The significant issue is how can we prevent these from undermining our capacity to live together on this planet? Or more positively, how can such differences contribute to planetary wellbeing? One answer to these daunting questions begins to take shape by shifting our focus from the differences themselves to the process by which they were created – from whether I can fly, or I have free will, for example, to how these ideas were created in the first place. Here begins the drama of social construction – a shift in the focus of attention to the origins, limits, and capacities of what we hold to be true, rational or good. Here we rise above the sea of meanings, to explore the process of making meaning itself. As the philosopher Nelson Goodman once queried, ‘If I ask about the world, you can offer to tell me how it is under one or more frames of reference; but if I insist that you tell me how it is apart from all frames, what can you say?’ In effect, all our accounts of the world emerge from some background or orientation, and here we can locate both the grounds for our understandings and the means of softening their boundaries. Indeed, by focusing on the way in which realities and values are fashioned, a path is opened to forming new and more promising visions of the real and the good. Differences do not demand conflict, and with care they can yield forms of life that expand the dimensions of wellbeing.

사회 구성주의적 의미 탐구의 기초에는 간단하고 명료한 제안이 있습니다. 우리가 세계를 이해하는 방식 – 즉, 우리가 현실적이고, 합리적이며, 선하다고 주장하는 것들 – 은 우리가 참여하는 사회적 과정에서 비롯된다는 것입니다. 그러나 이것은 시작에 불과합니다. 사회 구성의 논리를 탐구하기 시작하면, 흔히 받아들여지던 가정들이 흔들리기 시작합니다. 한 학생이 말했듯이, "구성주의적 아이디어에 빠지기 시작하면, 모든 가구가 창문 밖으로 날아가기 시작합니다." '현실', '객관성', '이성', '지식'과 같은 오랜 단어들에 대한 질문이 제기됩니다. 자신의 이해가 도전을 받고, 생각, 감정, 욕구까지도 의문에 휩싸이게 됩니다. 타인과의 관계도 새로운 차원을 얻게 됩니다. 공동체, 정부, 국제 관계의 의미가 새롭게 재구성될 것입니다. 갈등 또한 개인의 삶에서부터 국가와 지구에 이르기까지 새로운 관점에서 볼 수 있습니다. 그리고 그러한 활기를 주는 힘 덕분에, 구성주의적 아이디어와 실천은 이제 전 세계 모든 곳에서 탐구되고 있습니다. 부에노스아이레스에서 헬싱키까지, 런던에서 베이징까지, 뉴델리에서 케이프타운까지 여행하면, 활발한 논의와 유망한 실천 사례의 증가를 목격할 수 있습니다. 가구들이 움직이고 있는 것입니다.

일반적으로 사회 구성주의라고 불리는 아이디어 모음은 특정 개인에게 속하지 않습니다. 이 아이디어들은 특정한 책, 학문적 분야, 또는 직업에서 파생되거나 그 의미를 한정하지 않습니다. 오히려, 사회 구성주의적 아이디어는 학문과 실천을 넘나드는 광범위한 대화 과정에서 탄생합니다. 그리고 대체로, 대중의 큰 부분이 그 잠재력에 이미 민감하지 않다면, 이러한 아이디어들은 변화를 만들어내지 못할 것입니다. 학자와 실천가들은 차이를 만들어내기 위해서는 이미 그 차이가 중요하다고 여기는 청중이 필요합니다. 구성주의적 대화는 계속 진행 중이며, 누구에게나 – 이 책을 읽는 독자를 포함하여 – 열려 있습니다. 이것은 여러분이 참여하도록 초대받은 대화로 읽혀야 합니다. 또한, 사회 구성에 대해 다양한 관점과 긴장이 존재한다는 점도 상상할 수 있을 것입니다. 먼저 널리 공유되는 몇 가지 제안을 개괄한 뒤, 더 구체적인 발전으로 넘어가 보겠습니다.

At the base of this social constructionist inquiry into meaning lies a simple and straightforward proposal: our understandings of the world – what we claim to be real, rational, and good – emerge from the social process in which we participate. But that is only the beginning. When you begin to explore the logics of social construction, common assumptions are unsettled. As one student put it, ‘Once you get into constructionist ideas, all the furniture begins flying out the window.’ Questions are raised about such long honoured words as ‘reality’, ‘objectivity’, ‘reason’, and ‘knowledge’. One’s self understanding is challenged; one’s thoughts, emotions, and desires are all placed in question. Relations with others will also acquire a new dimension. The meaning of community, government, and international relations will be reformed. Conflict can be seen in a different light – from one’s personal life to the nation and the planet. And, because of their energizing power, constructionist ideas and practices are now explored in all corners of the world. You may travel from Buenos Aires to Helsinki, from London to Beijing, from New Delhi to Cape Town, and find both lively discussions and a burgeoning array of promising practices. The furniture is on the move.

The collection of ideas generally called social constructionist do not belong to any one individual. There is no single book, academic discipline, or profession from which they derive, or that circumscribes their meaning. Rather, social constructionist ideas emerge from a wide-ranging process of dialogue, cutting across disciplines and practices. And in large degree, these ideas would not make a difference if large segments of the public were not already sensitive to their potentials. Scholars and practitioners seldom make a difference unless there is already an audience for whom the difference is important. Constructionist dialogues remain ongoing and open to anyone – including readers of this book. You should read this as a conversation in which you are invited to participate. As you can also imagine, there are many different views of social construction, and some tensions among them. Let me first outline a number of widely shared proposals, and then we can turn to more detailed developments.

현실과 선의 사회적 기원

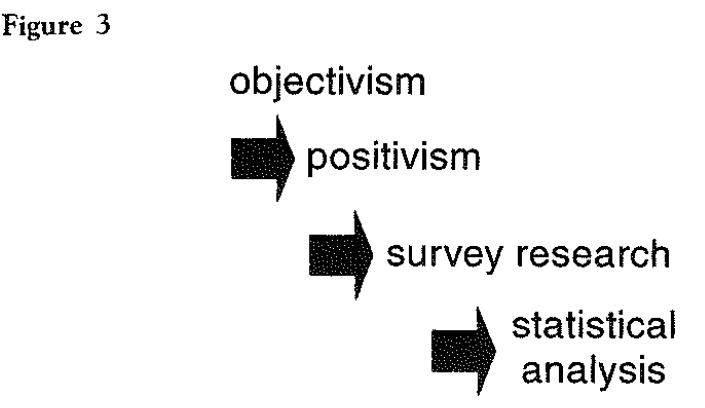

앞서 언급했듯이, 기본적인 구성주의 아이디어는 충분히 간단합니다. 하지만 더 넓은 드라마를 이해하기 위해서는 이러한 구성주의 아이디어가 사회 과학 분야에서 어떻게 발전했는지 추적하는 것이 유용합니다. 20세기에 등장한 경험적 과학의 가장 큰 약속은 세계에 대한 신뢰할 수 있고 편향되지 않은 지식을 제공할 잠재력에 있었습니다. 이러한 지식은 인류에게 그들의 운명을 통제할 수 있는 능력을 부여할 것이었습니다. 물리학과 화학 같은 분야에서의 성공 사례는 그 대표적인 예였습니다. 이들 분야에서는 물질의 근본에 대한 통찰을 얻을 수 있었고, 이러한 통찰은 의료, 에너지 생산, 교통 등 여러 분야에서 엄청난 진전을 가능하게 했습니다.

경험적 과학이 보편적 진리에 이르는 길이라는 낙관론이 폭발적으로 증가하면서 사회 과학의 발전이 촉진되었습니다. 자연과학의 논리와 연구 도구를 활용함으로써 심리학, 경제학, 사회학, 인류학과 같은 분야가 인간 생활에 무한한 혜택을 제공할 수 있을 것으로 믿어졌습니다. 자연과학의 논리를 적용하면, 궁극적으로 조화로운 세상과 모든 이의 번영을 이루는 것이 가능할 것이라고 여겨졌습니다. 이것은 시도할 가치가 분명히 있는 실험이었습니다.

과학적 지식을 확립하기 위한 기본 논리 – 종종 경험적, 즉 경험에서 유래한다고 불리는 – 는 충분히 단순합니다. 먼저 필요한 것은 세상을 신중하고 편향 없이 관찰하는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 주의 깊게 그리고 반복적으로 관찰하고 그 결과를 기록해야 합니다. 개인적인 가치관, 신념, 이념적 성향을 제쳐두고, 편견 없이 관찰할 수 있어야 합니다. 그 후에는 신중한 사고가 이어져야 합니다: 어떤 구분을 해야 할지, 어떤 패턴이 있는지, 사건들이 어떻게 연결되는지 등을 분석해야 합니다. 이상적으로는, 이러한 아이디어는 다른 사람들과 공유되어야 하며, 다른 이들이 자신의 관찰과 비교하여 여러분의 아이디어와 결과를 검증할 수 있어야 합니다. 검증이 여러분의 발견을 확증한다면, 추가적인 추론이 가능해지고 새로운 연구가 시작될 수 있습니다. 물론, 검증 실패는 잘못된 아이디어를 폐기할 수 있게 합니다.

THE SOCIAL ORIGINS OF THE REAL AND THE GOOD

As mentioned, the basic constructionist idea is simple enough. But to appreciate the broader drama it is useful to trace the way constructionist ideas developed for many of us in the social sciences. The great promise of empirical science as it emerged in the 20th century lay in its potential to yield reliable and unbiased knowledge of the world. Such knowledge was to grant humankind the capacity to control their destiny. Exemplary were the success stories in such fields as physics and chemistry. Here we seemed to gain insights into the fundamentals of matter, and such insights further enabled enormous strides to be made in healthcare, energy production, transportation and more.

It was this bursting optimism in empirical science as the route to universal truth that inspired the development of the social sciences. By employing the logics and research tools of the natural sciences, it was believed fields such as psychology, economics, sociology, and anthropology could bear fruits of unending nourishment to human living. By applying the logics of the natural sciences, we could ultimately achieve a world of harmony and the flourishing of all. This was surely an experiment worth trying.

The basic logic for establishing scientific knowledge – often called empirical, or deriving from experience – is simple enough. Required first is the careful and unbiased observation of the world. Look carefully and repeatedly, for example, and record the observations. Set your personal values, beliefs, and ideological leanings aside so that you can observe without bias. Observation is then followed by careful thought: what distinctions should be made, what are the patterns, how do events fit together? Ideally, these ideas should be shared with others, so that they can test your ideas and findings against their own observations. If the tests confirm what you have discovered, then further deductions may follow, and new research given birth. And of course, failures to confirm would allow false ideas to be cast aside.

사회과학 분야에서, 이러한 비전의 힘은 정량적 측정 도구와 통계 분석에 대한 의존으로 인해 더욱 강화되었습니다. 이러한 도구들은 연구 결과의 신뢰성과 타당성을 주장하는 근거를 제공했습니다. 체계적인 관찰과 신중한 사고를 통해, 우리는 사회 세계에 대한 가치 중립적인 진실에 다가갈 수 있을 것이고, 그러한 지식을 바탕으로 사회에서 빈곤, 갈등, 정신 질환을 없애고, 더 효과적인 교육, 범죄 통제, 조직 개발 등을 이루어낼 수 있을 것이라 믿었습니다.

이 논리의 요소들은 여전히 사회과학의 많은 영역에서 지배적인 위치를 차지하고 있습니다. 하지만 이 분야에서 일하던 많은 사람들에게 이러한 낙관적인 약속은 점차 쇠퇴하기 시작했습니다. 특히 20세기 후반, 반전 운동이 정부와 '군산복합체'에 대한 일반적인 불신을 촉발하면서, 과학의 권위에 대한 중요한 의문들이 제기되기 시작했습니다.

이러한 동요는 과학자들이 '부당한 전쟁'을 위한 무기 개발에 재능을 기여하고 있다는 사실에서 시작되었습니다. 경험적 과학에 대한 헌신이 도덕적 판단의 종말을 의미하는 것인가요? 사회과학에서는 이러한 문제가 보다 직접적으로 다가왔습니다. 예를 들어, 정신 건강의 경우, 정신의학 전문직은 동성애를 정신질환의 공식 분류(DSM)에 포함시켰습니다. 심지어 1973년 전문직 연례 회의에서 동성애가 정신질환인지 여부에 대한 투표가 진행되었고, 이 진단을 지지하는 의견이 압도적이었습니다. 제가 날 수 있는지에 대한 논의에서 언급했듯이, 숫자는 중요합니다!

이러한 권위 있는 진단에 대한 광범위한 저항에 더해, 과거 환자들은 왜 자신들이 정신질환자로 지정되었는지 질문하기 시작했습니다. 왜 목소리를 듣는 것(주로 조현병의 증상으로 진단됨)이 '질환'으로 불리며, 신경다양성에 대한 기여로 간주되지 않는 것인가요? 다른 분야에서는 인종 간 지능 차이를 주장하는 과학적 주장, 한부모 가정이 적절한 아동 발달을 저해한다는 주장, 남성이 여성보다 본질적으로 더 나은 리더라는 주장에 대한 저항이 있었습니다.

바로 이러한 저항들이 사회 구성주의에 대한 대화를 활성화시켰습니다. 왜 신중하게 통제된 관찰, 측정, 통계 등이 이렇게 이념적으로 논란이 되는 결론으로 이어졌을까요? 어떻게 그러한 결론을 신뢰할 수 있을까요? 이러한 진실은 누구의 것이었나요? 저항이 커지면서, 점차 몇 가지 공통된 합의점을 찾아볼 수 있었습니다. 이 중 다섯 가지는 이제 사회 구성주의에서 실질적인 작업 가정으로 자리 잡았습니다.

THE SOCIAL ORIGINS OF THE REAL AND THE GOOD

For us in the social sciences, the strength of this vision was also bolstered by a reliance on quantifiable tools of measurement tools and statistical analysis. Here lay the grounds for claims to the reliability and validity of our findings. Through systematic observation and careful thought, we should move toward and value neutral truths about the social world. With such knowledge in our grasp we could move toward ridding society of poverty, conflict, and mental illness; and creating more effective education, crime control, and organizations – for starters.

Elements of this logic still remain dominant in many areas of the social sciences. But for many of us who worked in these sciences, the optimistic promises of this logic began to decay. Particularly in the late 20th century, when anti-war protest was triggering a general distrust of government and the ‘military-industrial complex’, significant questions began to mount about the authority of science.

The rumblings began with the fact that scientists were contributing their talents to developing weapons for an ‘unjust war’. Does a commitment to empirical science mean the end of moral judgement? In the social sciences the issues were more immediately at hand. For example, in the case of mental health, the psychiatric profession had listed homosexuality in their official classification (DSM) of mental illnesses. Even in 1973 a vote was taken at the annual meeting of the profession on whether homosexuality was a mental disorder, and support for the diagnosis was overwhelming. Recall the discussion of whether I can fly: numbers matter!

Adding to the widespread resistance to this authoritative diagnosis, ex-patients also began to ask why they were designated as mentally ill. Why is hearing voices (commonly diagnosed as a symptom of schizophrenia) called an ‘illness’ as opposed to a contribution to neurodiversity? In other sectors, there was resistance to scientific claims that races differ in intelligence, that single parent households endanger proper child development, and that men are inherently better leaders than women.

It is just such resistances that energized the dialogues on social construction. Why were the carefully controlled observations, measures, statistics and so on leading to conclusions that were so ideologically inflaming? How could we trust such conclusions? Whose truths were these? As resistance grew, one could begin to locate a range of common agreements. Five of these have now become rough working assumptions in social construction.

1. 우리가 세계를 묘사하고 설명하는 방식은 ‘존재하는 것’에 의해 요구되지 않는다

여기서 경험주의적 지식 관점의 핵심 가정을 떠올려 보십시오: 우리는 세심한 세계 관찰에서 시작하며, 우리의 묘사와 설명은 ‘존재하는 것’에 의해 결정되어야 합니다. 통제된 관찰은 있는 그대로의 세계를 정확히 보여주는 그림을 제공해야 합니다. 이는 충분히 합리적으로 보이지만, 정신의학 전문직의 권위를 의문시하기 시작할 때, 인간의 다양한 활동들이 어떻게 ‘정신질환’이라는 이름으로 분류되었는지에 대한 질문이 생겨납니다. 움직이는 몸을 관찰하거나 그것의 말을 듣는 것에서 특정 라벨을 붙이는 것은 필수적이지 않습니다. 더 넓게 보면, 관찰 그 자체는 언어로 표현되는 방식에 아무런 요구를 하지 않습니다.

예를 들어, 우리가 동성애라고 부르는 것은 생물학적 기능의 자연스럽고 정상적인 변형, 라이프스타일 선택, 신의 창조물, 운명, 혹은 죄 등 다양한 것으로 불릴 수 있습니다. (참고로, 동성애는 1987년에 정신질환 목록에서 제외되었습니다.) 더 넓은 관점에서 보면, 우리는 정신질환을 관찰하는 것이 아니라, 정신질환이 존재하는 … 혹은 존재하지 않는 세계를 함께 만들어내는 것입니다.

비슷한 아이디어는 초기 라벨링 이론의 사회학에서도 나타났습니다. 예를 들어, 스스로 범죄 행위가 되는 것은 없다는 주장이 있습니다. 대신, 법전을 만들고, 경찰 조직을 세우고, 법정을 운영하며, 감옥을 설립함으로써 우리는 ‘범죄자’라고 부르는 것을 생산하는 시스템을 만들어낸 것입니다. 아이러니하게도, 법 집행은 범죄를 만들어냅니다! 마찬가지로, 학교는 낙제 학생을 만들어내고, 종교는 죄를 만들어냅니다. 이런 관점에서 보면, 우리는 이러한 라벨이나 구성들이 최선의 선택인지 물어볼 수 있습니다. 이것이 라벨링이나 분류를 포기해야 한다는 결론을 의미하지는 않습니다. 영어에서 이것은 명사를 사용하는 것을 포기하는 것과 같습니다. 하지만 우리가 이름을 붙이거나 묘사하는 모든 방식이 선택적이라는 점을 인식해야 합니다. 구성주의자들이 묻는 것은, 우리가 현재 사용하는 용어가 정말로 우리에게 적합한지에 대한 질문입니다.

더 넓은 의미에서, 이러한 관점에서 보면 어떤 상태나 상황에 대해 무한한 수의 묘사와 설명이 가능하다는 결론이 나옵니다. 그렇다면, 우리는 우리가 세상과 자신에 대해 배운 모든 것이 – 예를 들어, 중력이 지구에 우리를 붙잡아 둔다든가, 지구는 둥글다든가, 지구가 태양 주위를 돈다든가 하는 것 – 다르게 될 수도 있다는 점을 깨닫기 시작해야 합니다. ‘존재하는 것’에는 특정한 설명을 요구하는 요소가 없으며, 선택적 관찰을 통해 중력이 없고, 지구가 평평하며, 태양이 지구 주위를 도는 대안적인 세계를 언어로 구성할 수 있습니다.

많은 사람들에게 이러한 가정은 깊이 위협적입니다. 이는 초월적 진리 – 문화와 역사를 초월해 세계를 정확히 그려내는 말 – 가 없음을 암시할 뿐만 아니라, 우리가 붙잡을 수 있는 아무것도 없으며, 우리의 믿음을 근거로 삼을 확고한 토대도 없으며, 어떤 안정성도 없음을 시사합니다. 이는 우리를 구성주의의 두 번째 작업 가정으로 이끕니다.

1. The ways in which we describe and explain the world are not required by ‘what there is’

Recall here a key assumption in the empiricist view of knowledge: we begin with careful observation of the world; our descriptions and explanations should be driven by what there is. Controlled observations should provide an accurate picture of the world as it is. While this seems reasonable enough, in questioning the authority of the psychiatric profession, one begins to ask how it is that various forms of human activity became labelled as ‘mental illness’. There is nothing about watching a body in motion or listening to its utterances that demands or requires that particular label. Or more broadly, observation in itself demands nothing in the way it is represented in language.

What we call homosexuality, for example, could also be called a natural and normal variation in biological functioning, a lifestyle choice, God’s creation, destiny, or a sin … among other things. (Incidentally, homosexuality was dropped from the list of psychiatric disorders in 1987.) More broadly this means that we don’t observe mental illness; together we create a world in which mental illness exists … or not.

Much the same idea emerged in the early sociology of labelling. As argued, for example, there are no criminal acts in themselves. Rather, in establishing a legal code, a police force, courts of law, and prisons, we have created a system that produces what we call ’criminals’. In an ironic sense, law enforcement produces crime! In the same way, schools produce failing students, and religions produce sin. When put in these terms, we can ask whether these labels or constructions are our best options. This is not to conclude that labelling or categorizing should be abandoned. In English, this would be to abandon the use of nouns. But it is to recognize that all our ways of naming or describing are optional. As constructionists ask, are we well served by using the terms we now embrace?

There are broader implications. It follows from the above that for any state of affairs, a potentially unlimited number of descriptions and explanations is possible. If this is so, we must also begin to realize that everything we have learned about our world and ourselves – that gravity holds us to the earth, the world is round, the earth revolves around the sun, and so on – could be otherwise. There is nothing about ‘what there is’ that demands these particular accounts; with selective observation, we could use our language to construct alternative worlds in which there is no gravity, the world is flat, or the sun revolves around the world.

For many people this supposition is deeply threatening. Not only does it suggest that there is no transcendent truth – words that accurately map the world beyond culture and history, it also suggests there is nothing we can hold on to, nothing solid on which we can rest our beliefs, nothing secure… This leads us to a second constructionist working assumption.

2. 우리가 세계를 묘사하고 설명하는 방식은 관계의 결과물이다

정신질환을 진단하는 경우, 조현병, 신경성 식욕부진증, 강박 장애와 같은 용어들이 주로 정신의학 커뮤니티에서 비롯된다는 점을 쉽게 알 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, 물리학, 화학, 경제학, 법학, 의학, 농업 등 다양한 전문 분야에서도 공유되는 담론이 존재합니다. 더 넓은 수준에서 보면, 우리의 모든 세계 묘사와 설명은 우리의 관계에서 비롯된다는 점을 추적할 수 있습니다. 이는 언어 자체의 기원이 사회적이라는 원칙 때문에 그렇습니다. 혼자 고립된 한 사람의 발화는 언어를 구성하지 못하며, 본질적으로 무의미합니다. 두 명 이상의 사람들이 특정 발화, 표식, 제스처를 의미 있는 것으로 동의할 때만 그것들은 언어가 됩니다.

다시 한 번, 동의의 중요성을 주목하십시오. 언어를 창조할 가능성에는 거의 제한이 없습니다. 친구들끼리 공유하는 비밀 신호에서부터 세계 여러 언어에 이르기까지 다양합니다.

이는 본질적으로 우리의 언어가 세계의 그림이나 지도로 작동하지 않는다는 것을 의미합니다. 더 자세히 관찰한다고 해서 쉽게 수정될 수 있는 것이 아닙니다. 오히려, 언어는 우리가 함께 무언가를 하는 과정에서 나타납니다. 단어의 의미는 그것이 어떻게 사용되는지에 대해 우리가 합의한 방식에 따라 달라집니다. 여기서 20세기 철학자 루트비히 비트겐슈타인의 작업이 핵심적입니다. 그는 “단어의 의미는 그것이 언어에서 사용되는 방식이다”라고 제안했습니다. 따라서 동일한 단어가 서로 다른 사람들에게, 서로 다른 시점에 매우 다른 의미를 가질 수 있습니다.

예를 들어, 단어 ‘fire(불)’를 생각해 봅시다. 이 단어는 그림처럼 작용할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 우리가 산불(forest fire)이나, 그가 몸을 따뜻하게 하기 위해 불을 피웠다(he lit a fire)고 말할 때 특정 이미지를 떠올릴 수 있습니다. 하지만 단어의 다른 사용 사례를 살펴보면:

- Did he fire the pistol? (그가 권총을 발사했나요?)

- Do that again, and I will fire you! (그렇게 또 하면 너를 해고할 거야!)

- Come on baby, light my fire. (자기야, 내 열정을 불태워줘.)

- He lives on Fire Island. (그는 파이어 아일랜드에 산다.)

- Look at those wonderful fireflies. (저 멋진 반딧불 좀 봐.)

또한, 우리는 특정 단어들이 언제, 어디서 적절한지에 대한 합의를 발전시킵니다. 어떤 맥락에서는 잘 작동하지만, 다른 맥락에서는 그렇지 않을 수 있습니다. 이러한 사회적 규칙(형식적이든 비공식적이든)에 주목하며, 비트겐슈타인은 이를 "언어 게임"이라는 용어로 표현했습니다. 의미 형성은 규칙에 따라 이해를 창조해야 하는 게임 같은 특성을 지닙니다.

예를 들어, 우리가 참여하는 사회적 환경이 우리 대화를 지배하는 다양한 방식을 생각해 봅시다. 우리의 대화 패턴 – 단어와 구의 선택, 억양, 목소리의 크기 – 은 친구들과 파티를 하거나, 부모나 선생님과 이야기하거나, 어린 아이들과 놀거나, 영원한 사랑을 고백할 때 상황에 따라 달라집니다.

대학에서는 생물학의 언어 게임이 사회학, 경제학, 물리학의 언어 게임과 다릅니다. 각 학과의 구성원들은 특정한 언어 게임을 발전시켰으며, 규칙을 따르지 않으면 게임에서 배제될 수도 있습니다.

언어 사용 방식에 의미의 기원을 추적함으로써, 우리는 세 번째 작업 가정을 위한 토대를 마련하게 됩니다.

2. The ways in which we describe and explain the world are the outcomes of relationships

In the case of diagnosing mental illness, it is easy to see how words like schizophrenia, anorexia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder largely originate within the psychiatric community. Likewise, there is a shared discourse within fields of physics, chemistry, economics, law, medicine, farming, and other professions. On a broader level we can trace all our descriptions and explanations of the world to our relationships. This is so in principle because the origins of language itself are social. The utterances of a single isolated person do not constitute language; they are essentially nonsense. It is only when two or more people agree to treat certain utterances, markings, and gestures as meaningful that they become languages.

Note again the importance of agreement. There are few limits to the possible creation of languages – from the secret signals shared by friends to the many languages of the world.

This essentially means that our languages do not function as pictures or maps of the worlds that can be corrected simply by looking more closely. Rather, they emerge in the process of our doing things together. The meaning of a word thus depends on our agreements about how it is used. Here the work of the 20th-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein is pivotal. As he proposed, ‘The meaning of a word is its use in the language.’ It follows that the same word may mean many different things for different people at different times.

To illustrate, consider the word ‘fire’. Yes, the term can function like a picture. For example, we may have a particular image in mind when we say that there is a forest fire, or he lit a fire to keep him warm. But consider some other uses of the word:

- Did he fire the pistol?

- Do that again, and I will fire you!

- Come on baby, light my fire.

- He lives on Fire Island.

- Look at those wonderful fireflies.

We also develop agreements on when and where certain words are appropriate or not. They work well in some contexts, but not others. In calling attention to these social rules – both formal and informal – Wittgenstein coined the term language games. Meaning making has a game-like quality in requiring us to play by the rules in order to create understanding.

Consider for example, the various ways our talk is governed by the social settings in which we participate. Our patterns of talk – choices of words and phrases, intonation, and the volume of our voices will all vary depending on whether we are partying with friends, speaking with parents or teachers, playing with young children, or professing undying love. In our universities the language games of biology differ from those of sociology, economics, or physics. In each department, the participants have developed specific games of language, and if you don’t play by the rules, you may be excluded from the game.

By tracing the origins of meaning to the way we use language, we prepare the way for a third working assumption.

3. 세계에 대한 설명은 사회적 유용성에서 그 중요성을 얻는다

앞서 제안했듯이, 우리의 묘사나 이해를 주도하는 것은 세계 자체가 아닙니다. 오히려, 우리는 관계에 참여하며, 이러한 관계에서 이해의 어휘가 등장하고, 우리는 이를 바탕으로 세계를 묘사하고 설명합니다. 그러나 우리의 설명이 관계의 부산물이라고 하더라도, 왜 이렇게 많은 이해의 가능성이 존재하는지에 대한 질문이 생깁니다. 왜 세계에 대한 우리의 구성은 이렇게 전 세계적으로 다양할까요?

언어 게임이라는 아이디어가 이에 대한 통찰을 제공합니다. 앞서 제안했듯이, 다양한 사회적 환경에서 서로 다른 언어 규칙을 따르는 것이 사회적으로 유용합니다. 하지만 이것은 단순히 언어 게임만은 아닙니다. 언어 게임의 규칙은 행동의 규칙이나 관습에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다. 화학, 자동차 수리, 야구, 혹은 우정에 대한 우리의 논의는 단순히 언어의 게임이 아니라, 해당 환경에서 우리의 삶의 방식과 연결되어 있습니다.

이러한 삶의 방식에는 우리의 말과 행동뿐만 아니라, 다양한 물체, 공간, 환경도 포함됩니다. 예를 들어, 테니스에서 우리가 사용하는 언어 게임(‘서브’, ‘듀스’, ‘서티 러브’ 등의 단어 포함)은 선수들의 움직임뿐만 아니라 라켓, 공, 테니스 코트, 조명 등의 물리적 요소와도 관련되어 있습니다. 비트겐슈타인은 이 모든 관계 배열 – 단어, 행동, 물체 – 을 삶의 형태라고 불렀습니다. 우리는 이를 문화적 전통이라고 부를 수도 있습니다. 교실에서 함께하는 활동은 하나의 삶의 형태이며, 저녁 파티, 생물학 연구실에서의 작업, 혹은 사랑에 빠지는 일도 마찬가지입니다.

우리의 언어적 구성물이 삶의 형태에 뿌리를 두고 있다는 것을 이해하는 것은 매우 유용합니다. 먼저, 우리가 세계를 구성하는 데 사용하는 용어가 어떻게 생겨났는지 이해할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 왜 이누이트족은 따뜻한 지역에 사는 사람들보다 눈(snow)을 나타내는 더 많은 단어를 가지고 있을까요? 그것은 이러한 구분이 북극에 사는 사람들에게 유용하기 때문입니다. 이러한 구분은 그들이 주변 환경에 대한 관점을 바탕으로 행동을 더 신중하게 조정할 수 있게 하며, 심지어 생명을 구할 수도 있습니다. 대부분의 경우, 세계 구성과 사회적 유용성은 밀접하게 연결되어 있습니다. 네 번째 제안은 이러한 점을 상호 조건으로 제시합니다.

3. Accounts of the world gain their significance from their social utility

As proposed, it is not the world that drives our descriptions or understandings. Rather, we participate in relations from which emerge vocabularies of understanding, and we describe and explain the world in these terms. Yet, while our accounts are the byproduct of relationships, the question now emerges as to why we have so many possibilities for understanding? Why are there such global variations in our constructions of the world?

The idea of the language game provides insight. As just proposed, it is socially useful to play by different rules of language in various social settings. But clearly these are not simply language games alone. The rules of the language games are embedded in rules or conventions of action. Our discussions of chemistry, auto repair, baseball, or friendship are not simply games of language; they are tied to our ways of life within these settings.

These ways of life include not only our words and actions, but also the various objects, spaces, and environments around us as well. Thus, for example, the language game we use in tennis – including such words as ‘serve’, ‘deuce’, and ‘thirty love’ – is related not only to the movements of the players, but also to the fact that they have racquets, balls, a tennis court, and available light. Wittgenstein called the entire array of relationships – words, actions, objects – a form of life. We might otherwise call them cultural traditions. What we do in a classroom together is thus a form of life, as is a dinner party, working in a biology research lab, or having a love affair.

Understanding that our linguistic constructions are embedded in forms of life is very helpful. At the outset, we can appreciate how the terms in which we construct the world come into being. Why, for example, do Inuit have more words for snow than people who live in warmer climes? It is because these distinctions are useful for those who live in the Arctic. They can adjust their behaviour more carefully to their view of the surrounding conditions; the distinctions could even be life-saving. For the most part, world construction and social utility are closely allied. A fourth proposal stands as a corollary.

4. 진리에 대한 주장은 삶의 형태 내에서 그 유용성을 얻는다

이 모든 것이 객관성, 정확한 측정, 그리고 진리 자체의 종말을 의미하는 것일까요? 그렇지는 않지만, 사회 구성주의적 아이디어는 중요한 한계를 지적합니다. 앞서 보았듯이, 언어를 세계의 그림, 지도, 또는 반영으로 간주하는 전통적 관점에는 중요한 결함이 있습니다. 어떤 언어가 다른 언어보다 진리에 더 가까운 것으로 간주될 정당한 이유는 없습니다. 어떤 상황에서도 다수의 구성이 가능하며, 사회적 관습 외에는 어떤 것이 현실의 본질에 더 잘 부합한다고 선언할 수 있는 방법이 없습니다. 세계와 단어 간에는 특권적인 관계가 없습니다.

그러나 이것이 우리가 진실과 거짓을 구분할 수 없다는 결론으로 이어지거나, 더 극단적으로는 세계에 대한 모든 묘사가 동등히 유효하다는 것을 의미하지는 않습니다. 만약 그렇다면, 뉴스 보도, 일기예보, 혹은 과학적 발견의 지위는 어떻게 될까요? 만약 단어가 세계를 반영하거나 그리는 것이 아니라면, 음주 운전이 위험하다는 경고나 토네이도가 다가오고 있다는 경고를 어떻게 의미 있게 전달할 수 있을까요? 우리가 병에 걸렸을 때, 대부분의 사람들은 자동차 정비사나 수학자보다는 훈련된 의사의 설명을 선호할 것입니다. 우리의 일상 생활에서 모든 묘사가 동등한 것은 아닙니다. 어떤 것은 정확하고 유익한 반면, 다른 것은 터무니없거나 환상적입니다. 사회 구성주의적 관점에서 이것을 어떻게 이해해야 할까요?

여기에서 언어가 우리의 다양한 삶의 형태에서 그 유용성으로부터 의미를 얻는다는 제안으로 돌아갑시다. 우리가 어떤 묘사가 ‘정확하다’(‘부정확하다’와 반대로)거나 ‘참이다’(‘거짓이다’와 반대로)라고 말할 때, 우리는 그것이 세계를 얼마나 잘 묘사하는지 평가하는 것이 아닙니다. 대신, 우리는 그 단어들이 특정한 삶의 형태 – 또는 더 일반적으로, 특정 그룹의 관습 – 내에서 ‘진실을 말하는’ 역할을 한다고 말하는 것입니다.

예를 들어, 축구 경기에서는 ‘페널티킥’이라는 말을 사용하며, 페널티킥이 언제 발생하는지에 대해 의문의 여지가 없습니다. 이 용어는 공정한 경기 진행에 매우 유용하며, 게임의 관습 내에서는 완전히 정확하게 사용될 수 있습니다. 마찬가지로, ‘세상은 둥글고 평평하지 않다’라는 주장은, 그림적 가치 – 즉, ‘존재하는 것’과의 일치 – 면에서는 참도 거짓도 아닙니다. 그러나 현재의 기준에 따르면, 캔자스에서 쾰른으로 비행할 때는 ‘둥근 세계의 진리’ 게임을 하는 것이 더 받아들여질 수 있으며, 캔자스 주를 운전할 때는 ‘평평한 세계의 진리’를 따르는 것이 더 유용할 수 있습니다.

세계가 원자로 구성되어 있다는 것도 어떤 게임을 초월해서 참인 것은 아닙니다. 하지만, 원자와 관련된 대화는 우리가 핵에너지라고 부르는 실험을 수행할 때 매우 유용합니다. 마찬가지로, 특정 종교적 삶의 형태 내에서는 사람들이 영혼을 가지고 있다고 적절히 말할 수 있습니다. 원자의 존재는 영혼의 존재와 보편적 의미에서 더 참되거나 덜 참되지 않습니다. 각각은 특정 삶의 형태 내에서의 현실입니다.

4. Truth claims acquire their utility within forms of life

Does all this mean the end of objectivity, accurate measurement, and truth itself? No, but social constructionist ideas do point to important qualifications. As we have seen, there are significant flaws in the traditional view of language as a picture, map, or reflection of the world. There is no justification in the view that some languages are closer to the truth than others. For any situation multiple constructions are possible, and there is no means outside social convention of declaring one as corresponding to the nature of reality better than another. There is no privileged relationship between world and word.

However, this does not permit the conclusion that we can’t distinguish between true and false accounts, or more radically, that any description of the world is as good as any other. If this were so, then what is the status of news reports, weather reports or scientific findings? If words don’t correspond or picture the world, then how can we meaningfully warn each other that drinking and driving are a dangerous combination, or that a tornado is on its way? If we become ill, most of us would prefer the account of the trained physician to that of an auto mechanic or mathematician. In our daily lives all descriptions are not equal; some are accurate and informative while others are fanciful or absurd. How are we to understand this from a constructionist perspective?

Here let’s return to the proposition that language gains its meaning from its utility in our various forms of life. When we say that a certain description is ‘accurate’ (as opposed to ‘inaccurate’) or ‘true’ (as opposed to ‘false’) we are not judging it according to how well it pictures the world. Rather, we are saying that the words have function as ‘truth telling’ within a particular form of life – or more generally, according to certain conventions of certain groups.

In the sport of soccer, we talk about ‘penalty kicks’, and there is no question about when a penalty kick is occurring. The term is very useful to playing the game in a fair manner, and it can be used with complete accuracy within the conventions of the game. In the same way, the proposition that ‘the world is round and not flat’ is neither true nor false in terms of pictorial value, that is, correspondence with ‘what there is’. However, by current standards, it is more acceptable to play the game of ‘round-world-truth’ when flying from Kansas to Cologne; and more useful to ‘play it flat’ when driving across the state of Kansas itself.

Nor is it true beyond any game that the world is composed of atoms; however, ‘atom talk’ is extremely useful if you are carrying out experiments on what we call nuclear energy. In the same way, we can properly say that people do indeed have souls, so long as we are participating in a form of life within certain religious circles. The existence of atoms is no more or less ‘true to the world’ than the existence of souls in any universal sense; each is a reality within a particular form of life.

이 맥락에서 우리는 왜 ‘진리’라는 용어가 우리의 삶에서 필수적이지만, 동시에 잠재적으로 위험할 수 있는지를 이해하게 됩니다. 진리는 특정 삶의 형태 내에서 유용한데, 이는 참가자들의 규칙이나 관습에 따라 무언가가 사실임을 확증하기 때문입니다. 이는 참가자들이 자신들에게 가치 있는 방식으로 행동을 조정하는 데 도움을 줍니다. ‘진리’(truth)와 ‘신뢰’(trust)라는 단어가 어원적으로 연결되어 있다는 사실은 놀랍지 않습니다. 사실, ‘~이 사실이다’라고 말하는 것은 다른 이들에게 당신을 신뢰하라는 초대와 같습니다.

예를 들어, 생화학자들이 아미노산에 대한 실험 결과를 보고할 때, 그들은 생화학 규칙에 따라 생화학자들이 세계에 대해 받아들이는 지식에 기여하고 있습니다. 연구자들은 다른 생화학자들이 그 결과를 신뢰할 것이라고 가정합니다. 다른 사람들이 동일한 실험을 반복하면 동일한 결과를 얻을 것입니다.

그러나 동시에, ‘진리’라는 선언이 특정 전통 내의 맥락에서 벗어나 모든 사람을 위한 진리로 주장될 때, 억압과 갈등의 가능성이 발생합니다. 예를 들어, 죽음에 대한 생물학적 정의를 받아들이는 것은 죽음이라는 개념이 사람들에게 갖는 풍부한 의미를 급격히 축소시킵니다. 사랑이 단순히 신경학적 상태라고 선언하는 것은 이 용어의 문화적 중요성을 박탈하는 것입니다. 또한, 특정 종교가 ‘유일한 진정한 신’을 대표한다고 선언하는 것은 갈등의 신호일 수 있습니다.

진리라는 이름으로 세계는 고문, 살인, 집단학살을 목격해 왔습니다. 모든 사람, 모든 시대를 위한 보편적 진리라는 개념을 버리고, 다양한 사람들이 다양한 시점에서 조화롭게 살아갈 수 있도록 다양한 진리로 이를 대체합시다. 따라서 구성주의적 관점은 실용적 현실주의에 기반합니다.

In this context we come to see why the term ‘truth’ is both essential to our lives, but potentially dangerous. It is useful within any given form of life because it affirms that something is the case according to the rules or conventions of the participants. It helps the participants coordinate their actions in ways that are valuable to them. It should not be surprising that the word ‘true’ and ‘trust’ are linked in their etymology. In effect, to say, ‘it is true that…’ is an invitation for others to place their trust in you.

Thus, if biochemists report the results of an experiment on amino acids, they are contributing to what biochemists take to be knowledge of the world – according to the rules of biochemistry – and the researchers presume that other biochemists will trust the results. If the others repeat the experiment, they will find the same results.

At the same time, however, when declarations of ‘truth’ leap from their location within a specific tradition, and are pronounced as Truth for all, we confront the possibilities for oppression and conflict. In accepting the biological definition of death, for example, we radically reduce the richness of its meaning for people. To proclaim that love is simply a neurological condition is to rob the term of cultural significance. And, to proclaim that a given religion represents the ‘one true god’ is a signal of conflict to come.

In the name of Truth the world has witnessed torture, murder, and genocide. Let us abandon the idea of Truth (universal, for all people at all times), and replace it with multiple truths, useful for harmonious living for various peoples at various times. The constructionist orientation, then, is one of pragmatic realism.

5. 가치 부여 과정은 삶의 형태 안에서 시작되고 지속된다

우리가 서로 관계를 맺고, 언어를 발전시키며, 신뢰받는 생활 방식을 형성함에 따라, 가치 부여의 관행이 등장합니다. 이러한 관행 중 대부분은 암묵적입니다. 그것들은 단순히 ‘우리 방식’으로 존재합니다. 누군가가 버스를 기다리는 긴 줄을 끼어들거나, 거지에게 욕설을 하거나, 고급 레스토랑에서 큰 소리로 말한다면 우리는 짜증이 날 수 있습니다. 이러한 행동을 비난하는 서면 규칙은 없지만, 그것들은 많은 문화에서 받아들여지는 삶의 방식을 위반합니다.

마찬가지로, 한 커플이나 가족은 자신들만의 관계 방식 – ‘우리 방식’ – 을 발전시킬 수 있으며, 이는 소셜 미디어에 계속 몰두하는 십대나 항상 늦게 귀가하는 배우자를 꾸짖는 형태로 나타날 수 있습니다. 일탈자를 처벌할 때, ‘우리 방식’이 ‘옳은 방식’이 되었다는 점이 명백해집니다.

우리는 비공식적인 규칙이 위협받거나 붕괴될 때 주로 가치 담론을 명시적으로 제시하며, 이를 규칙이나 법의 형태로 설명합니다. 윤리 담론은 주어진 삶의 형태를 확언하거나 방어하는 데 유용합니다. 앞서 논의와 맥을 같이하여, 우리는 정직에 높은 가치를 두는 이유가 주로 거짓말이 삶의 방식을 위협하기 때문이라는 점을 알 수 있습니다. 같은 방식으로, 예를 들어, 정부가 우리가 중요하게 여기는 활동을 제한하거나 방해할 때 우리는 자유, 인권, 혹은 존엄성을 찬양할 수 있습니다. 우리는 항상 우리가 살고 있는 전통에 의해 제약을 받지만, 자유에 대한 외침은 그 전통이 다른 가치의 전통에 참여하는 것을 방해할 때 주로 나오게 됩니다. 완전한 자유가 주어진다면, 할 일이 아무것도 없을 것입니다.

더 넓게 보자면, 이것은 가치가 사회적으로 협상된 성취물이라는 것을 암시합니다. 이런 의미에서, 관대함, 연민, 사랑, 평화, 그리고 삶 자체의 가치는 인간 본성에 내재된 것이 아닙니다. 이것들은 우리가 함께 살아가는 과정에서 발전시킨 용어들입니다. 삶에서 가치를 찾으려는 탐구는 자기 자신 안을 들여다보거나 하늘을 올려다보는 데서 발견되는 것이 아니라, 관계의 매트릭스 안에서 찾아야 합니다.

동시에, 종교, 국가, 혹은 전통의 가치를 유지하는 것은 지속적인 의미 형성 과정에 의존합니다. 대화가 끝나는 것은 가치의 소멸을 의미합니다.

간략히 요약하자면, 우리가 지식이라고 여기는 것은 고립된 개인이 세상을 관찰하고 있는 그대로 기록하는 데서 시작하지 않습니다. 오히려, 우리가 세계와 직면할 때 우리의 묘사와 설명은 관계 속에서 우리의 존재로부터 나타납니다. 우리의 관계 속에서 우리는 세계(그리고 우리 자신)의 본성에 대한 어휘, 가정, 이론을 발전시킵니다. 이러한 관계는 또한 특정 가치를 명시적 또는 암묵적으로 선호합니다. 우리가 세계에 대해 지식으로 여기는 것은 이 전통들의 가치를 담고 있으며, 우리의 탐구와 현실, 이성, 선에 대한 이해를 형성합니다.

이러한 제안은 충분히 합리적으로 보일 수 있습니다. 그러나 항상 그렇게 간주되었던 것은 아닙니다. 이러한 아이디어는 엄청난 논란의 대상이 되어 왔습니다(9장을 참조하십시오). 그리고 이러한 아이디어는 갑자기 어디선가 등장한 것이 아닙니다. 실제로, 사회 구성주의적 아이디어가 발전하고 꽃피운 것은 최근 몇십 년 사이에 이르러서야 가능했습니다. 많은 사람들은 이러한 발전의 뿌리를 학문적 세계의 주요 변화에서 찾을 수 있다고 봅니다. 이러한 변화를 이해하면 위에서 설명한 작업 가정에 중요한 차원을 더할 수 있으며, 혁신적인 함의에 대한 더 큰 통찰을 제공할 것입니다. 이러한 아이디어를 탐구한 후, 우리는 세계적 웰빙에 대한 함의로 전환할 것입니다.

5. The process of valuing originates and is sustained within forms of life

As we relate together, develop languages, and trusted patterns of living, so emerge practices of valuing. Most of these practices are implicit; they are simply present in ‘our way of doing things’. If someone breaks into a long line waiting for a bus, curses at a beggar, or talks loudly in a classy restaurant, we could be irritated. There are no written rules that condemn such behaviours, but they violate the accepted ways of life within many cultures.

In the same way, a couple or a family may develop their own patterns of relating – ‘our way’ – and thus scold the adolescent who is constantly grazing on social media, or the spouse who is always coming home late. Whenever deviants are punished, it is apparent that ‘our way’ has become ‘the right way’.

We articulate a discourse of value – spell it out in terms of rules or laws – primarily when informal rules are threatened or break down. The discourse of ethics is thus useful in either affirming or defending a given form of life. Echoing an earlier discussion, we place a strong value on honesty largely because lying represents a threat to a way of life. In the same way, for example, we may celebrate freedom, human rights, or dignity when governments constrain or prevent activities about which we care. We are always constrained by the tradition in which we live, but the cry of freedom is seldom voiced until that tradition prevents us from participating in another tradition of value. With complete freedom, there is nothing to do.

Broadly speaking, this first suggests that values are socially negotiated achievements. In this sense, the values of generosity, compassion, love, peace, and indeed life itself, are not intrinsic to human nature. These are terms we have developed in the course of living together. The quest for value in one’s life is not to be found by looking inward to the self, or upward to the heavens, but within the matrix of relations.

At the same time, sustaining the value of a religion, a nation, or a tradition relies on a continuous process of meaning making. The end of conversation signifies the demise of value.

To briefly summarize, what we take to be knowledge does not begin with the lone individual observing and recording the world for what it is. Rather, as we confront the world, our descriptions and explanations emerge from our existence in relationships. It is within our relationships that we foster our vocabularies, assumptions, and theories about the nature of the world (including ourselves). These relationships also favour certain values, either explicit or implicit. What we take to be knowledge of the world will carry the values of those traditions, and fashion our inquiry and understandings of reality, reason, and goodness.

These proposals may seem reasonable enough. However, they have not always been regarded as such. They have been the subject of enormous controversy (see Chapter 9). And they did not suddenly spring from nowhere. In fact, it is only within recent decades that social constructionist ideas have evolved and flowered. For many, the roots of this flowering can be traced to major shifts in the scholarly world. An understanding of these shifts will add significant dimensions to the working assumptions just described. It will also provide greater insight into the revolutionary implications. Following this exploration into ideas, we shall turn to the implications for global wellbeing.

사회 구성에 기반한 대화

제 관점에서 현대 구성주의는 각각 독립된 연구 영역에서 등장한 세 가지 주요 학문적 흐름에서 많은 영향을 받습니다. 이러한 사고의 흐름들은 한때 해당 학문 내에서 ‘뜨거운’ 주제였습니다. 그러나 시간이 지나면서 학자들은 이러한 영역들 간에 공통점을 발견하기 시작했습니다. 이는 모두가 동의했다는 것을 의미하지는 않습니다. 이러한 연구 영역들 사이의 긴장은 여전히 존재합니다. 그러나 이러한 아이디어들의 결합된 힘은 현대 사회 구성주의의 근간을 제공했을 뿐만 아니라, 우리가 곧 보게 될 글로벌 변혁의 토대를 마련했습니다. 아래는 이러한 발전들에 대한 간략한 개요일 뿐이며, 호기심 많은 독자는 이 장의 끝에서 추가 자료를 찾아볼 수 있습니다.

이데올로기적 비판: 누구의 이익을 위한 것인가?

앞서 제안했듯이, 가치로부터 자유로운 사실의 진술은 존재하지 않습니다. 50년 전만 해도, 과학, 뉴스 보도, 법정 등에서 사실에 대한 편향되지 않은 설명이 가능하다는 견해가 매우 강했기 때문에 이러한 제안을 이해하기 어려웠을 것입니다. 오늘날 우리의 이해는 학문적 발전에 크게 의존하고 있습니다. 이러한 영향을 초기 마르크스주의 문헌에서 찾을 수 있습니다.

마르크스가 제안한 바와 같이, 자본주의 경제 이론은 경제 세계를 정확히 읽어내는 방식으로 자신을 제시합니다. 그러나 이 이론은 그 옹호자들에게 유리한 시스템을 지지하기 때문에 의심받아야 합니다. 이 이론은 ‘가진 자들(haves)’이 ‘못 가진 자들(have-nots)’의 착취된 노동을 통해 계속해서 이익을 얻는 상태를 합리화합니다. 마르크스의 용어로 표현하자면, 자본주의 이론은 겉으로는 중립적이고 객관적으로 보이지만 대중을 현혹시켜 그들을 노예 상태로 유지하게 만드는 거짓말을 믿게 만듭니다.

마르크스는 종교적 권위에 대해서도 유사한 주장을 제기했습니다. 마르크스에 따르면, 종교적 가르침은 영적 세계를 밝혀주는 것이 아니라, ‘대중의 아편’으로 작용하여 억압과 착취에 대한 의식을 감소시킵니다.

비판의 논리는 중요합니다. 이는 설명의 내용을 문제 삼는 것이 아니라, 그것이 봉사하는 이익을 밝히거나 의문을 제기함으로써 그 정당성을 도전합니다. 누군가가 진리, 증거, 혹은 이성을 주장하더라도, 비판자는 묻습니다: 누가 이 설명으로 이익을 얻고, 누가 피해를 입으며, 누가 침묵하거나 착취당하거나 지워지고 있는가?

과학자, 학자, 대법원 판사, 혹은 뉴스 해설자이든, 이들은 모두 자신들이 봉사하는 이익, 가치, 교리, 혹은 정치적 목표를 지적하는 비판에 노출될 수밖에 없습니다.

Grounding Dialogues in Social Construction

In my view, contemporary constructionism draws heavily from three major lines of scholarship, each emerging in a separate domain of study. These lines of thinking were once ‘hot’ within these circles. However, with time scholars also began to find resonance across the domains. This did not mean that all agreed; tensions among these areas of study remain today. However, the combined force of these ideas not only provided the backbone for contemporary social constructionism, but as we shall see, laid the groundwork for global transformation. The following is only a sketch of these developments, but the curious reader will find additional suggestions at the chapter’s end.

Ideological Critique: Whose Interests Are Served?

As proposed, there are no statements of fact that are value-free. Fifty years ago it would have been difficult to make sense of that proposal, so strong was the view that in science, news reporting, and courts of law, for example, unbiased accounts of the facts were possible. Our understanding today owes a great deal to academic developments. One could trace the influence to early Marxist writings.

As Marx proposed, capitalist economic theory offers itself as an accurate reading of the world of economics. However, because the theory favours a system in which its proponents are benefited, it is suspicious. The theory rationalizes a condition in which the ‘haves’ continue to profit through the exploited labour of the ‘have-nots’. Or in Marxist terms, although seemingly neutral and objective, capitalist theory mystifies the public, leading people to believe a falsehood that keeps them enslaved.

Marx mounted a similar argument against religious authority. Religious teachings, as Marx proposed, do not illuminate the world of the spirit; rather, religion serves as an ‘opiate of the masses’, diminishing the consciousness of suppression and exploitation.

The logic of the critique is important: it challenges the legitimacy of an account not in terms of its content, but by questioning or illuminating the interests it serves. Regardless of one’s claims to truth, evidence, or reason, the critic asks: who is benefited by the account, who is harmed, or who is being silenced, exploited, or erased?

Whether a scientist, scholar, Supreme Court judge, or news commentator, all are subject to critique that points to the interests, values, doctrines, or political aims that they serve.

과학에 대한 비판 중 가장 중요한 흐름 중 하나는 과학이 이데올로기에 영향을 받지 않는 것처럼 보인다는 점에 초점이 맞춰져 있습니다. 과학자들은 이데올로기적으로 투자되지 않은 것처럼 보이고, 그들의 연구 결과는 공적 검증을 받을 수 있으며, 그들은 공공의 신뢰를 정당하게 얻었습니다. 그러나 비판적 관점에서 보면, 과학의 이러한 중립적인 외관이 가장 오해를 불러일으키고, 가장 현혹적이라는 것입니다. 따라서 비판적 검토가 필수적입니다.

이와 관련하여, 에밀리 마틴(Emily Martin)이 의학 교과서가 여성의 신체를 묘사하는 방식을 분석한 내용을 고려해봅시다. 그녀의 분석에 따르면, 여성의 신체는 주로 ‘공장’으로 묘사되며, 그 주된 목적은 종족 번식이라는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 생리와 폐경의 과정은 ‘비생산적인’ 시기로 간주되며, 낭비적이고 심지어 비정상적인 것으로 묘사됩니다.

이를 예로 들어, 표준 교과서가 생리를 설명하는 부정적인 표현들을 주목해 보십시오(이탤릭체는 강조):

- "프로게스테론과 에스트로겐의 혈중 농도 감소는 고도로 발달된 자궁내막 조직이 호르몬 지원을 상실하게 만든다."

- 혈관의 ‘수축’은 ‘산소와 영양분 공급의 감소’로 이어진다.

- ‘분해가 시작되면 전체 내막이 벗겨지기 시작하며 생리 흐름이 시작된다.’

또 다른 교과서는 생리를 "아기를 가질 수 없어서 자궁이 우는 것"으로 묘사하기도 합니다.

에밀리 마틴의 주요 주장

- 과학적 설명은 중립적이지 않다

마틴은 이러한 과학적 묘사가 전혀 중립적이지 않다고 주장합니다. 이러한 설명들은 은연중에 독자들에게 생리와 폐경이 고장이나 실패의 형태라는 메시지를 전달합니다. 이러한 부정적인 함의는 광범위한 사회적 결과를 가져옵니다.

- 여성은 이러한 설명을 받아들이면 자신의 몸과 소외감을 느낄 수 있습니다.

- 생리를 하는 성인기 대부분의 기간 동안, 그리고 가임기를 지난 후에는 영구적으로, 여성은 이러한 묘사에 따라 자신을 부정적으로 판단할 수 있습니다.

- 자녀가 없는 여성은 ‘비생산적’이라는 이유로 암묵적으로 비난받게 됩니다.

- 대안적 묘사가 가능하다

이러한 부정적인 묘사는 ‘존재하는 그대로의 현실’을 반영하는 것이 아니며, 여성의 역할을 ‘아기 제조기’로 축소하는 남성적 이익과 이데올로기를 반영합니다.

남성 신체에 대한 묘사의 차별성

마틴은 이러한 주장을 뒷받침하기 위해, 남성에게만 해당되는 신체 과정도 비슷하게 묘사할 수 있지만 그렇지 않다는 점을 지적합니다. 예를 들어, 사정의 경우, 정액은 남성의 관을 통과하면서 벗겨진 세포를 흡수합니다. 그러나 생물학 교과서는 사정을 설명할 때 남성이 세포를 ‘잃는다’거나 ‘낭비한다’는 언급을 하지 않습니다.

결론

마틴에 따르면, 생물학적 과학에서 지배적인 선택은 남성의 이익을 반영하며, 이는 여성에게 불리하게 작용합니다. 생물학적 과정에 대한 다양한 묘사가 가능함에도 불구하고, 현재의 묘사는 특정 이데올로기를 지지하며 여성의 역할과 경험을 축소합니다.

One of the most significant lines of such critique has been directed toward the sciences.

Scientists don’t seem to be ideologically invested; their findings are open to public scrutiny, and they have rightfully earned the public trust. Yet, for the critic, it is this seeming neutrality of science that is most misleading, most mystifying. Critical scrutiny is essential. In this light, consider Emily Martin’s analysis of the ways in which medical textbooks characterize the female body.

She concludes from her analysis that a woman’s body is largely portrayed as a ‘factory’ whose primary purpose is to reproduce the species. Thus, for example, the processes of menstruation and menopause are characterized as wasteful if not dysfunctional, for they are periods of ‘nonproduction’.

To illustrate, note the negative terms in which standard texts describe menstruation (italics mine):

- “The fall in blood progesterone and estrogen deprives the highly developed endometrial lining of its hormonal support.”

- "Constriction of blood vessels leads to a diminished supply of oxygen and nutrients.”

- "When disintegration starts, the entire lining begins to slough, and the menstrual flow begins.”

Another text says that menstruation is like “the uterus crying for lack of a baby.”

Martin’s Key Points

- Scientific descriptions are not neutral

- These descriptions subtly inform the reader that menstruation and menopause are forms of breakdown or failure.

- Women who accept these accounts may alienate themselves from their bodies, judge themselves negatively during menstruation, and feel condemned for childlessness.

- Alternative descriptions are possible

- These negative portrayals are not required by ‘the way things are’; they reflect masculine interests and an ideology reducing women to ‘baby makers.’

Disparity in Descriptions of Male Processes

Martin secures her case by pointing out that bodily processes exclusive to men could also be described in negative terms but are not. For example, during ejaculation, seminal fluid picks up cells that have been shed as it flows through male ducts. However, biological texts do not describe this as men ‘losing’ or ‘wasting’ cells.

Conclusion

For Martin, the dominant descriptions in biological sciences reflect male interests at the expense of women. Despite the availability of many possible descriptions, the current choice supports an ideology that diminishes women’s experiences and roles.

이와 같은 비판적 분석은 이제 대부분의 학문 분야에서 발견되며, 문화 연구와 같은 새로운 학문 분야는 광범위한 문화 생활의 패턴에 대해 비판적인 시각을 제시합니다. 이러한 분석은 특히 주변화되거나 억압받고, 잘못 표현되거나 사회 전체에 의해 ‘들리지 않는’ 소수자들에게 유용했습니다. 예를 들어, 미국에서는 아프리카계 미국인, 원주민, 아시아계 및 라틴계 미국인, LGBT+ 커뮤니티 구성원, 종교적 근본주의자, 아랍계 활동가 등이 이에 해당됩니다. 모든 경우에서 이러한 비판은 지배적인 문화의 당연하게 여겨지는 논리나 현실에 의문을 제기하며, 그것이 지배 집단의 이익을 어떻게 지원하고 불의를 지속시키는지 보여줍니다. 미국의 비판적 인종 이론은 일상적인 사회 관습과 제도에 내재된 인종차별적 함의를 탐구하며 대중의 주목을 끌어왔습니다. 예를 들어, 정의, 교육, 건강의 제도들이 체계적으로 흑인 공동체에 불이익을 준다는 점이 제기되었습니다. 투표 보안을 보호한다고 주장되는 법률은 실제로는 소수자들의 투표를 억압하는 수단으로 기능하고 있습니다. 또한, 정책 입안자들이 ‘모두가 동등한 기회를 갖도록 보장하기 위해’ 사용한다고 주장하는 국가 교육 시험은 실제로는 재정적, 학문적으로 특권을 가진 사람들에게 유리합니다. 우리는 곧 이념적 비판의 함의에 대해 다시 논의할 것입니다. 그동안, 구성주의 연구의 두 번째 지적 원천으로 눈을 돌려봅니다.

Critical analyses such as these are now found across most academic disciplines,

with new disciplines such as cultural studies placing a critical eye on wide-ranging patterns of cultural life.7 Such analyses have been especially useful for minorities who find themselves marginalized, oppressed, misrepresented, or ‘unheard’ by society at large – in the United States, for example, by African Americans, Native Americans, Asian and Latino-Americans, members of the LGBT+ community, religious fundamentalists, and Arab activists, to name but a few. In all cases, the critique calls into question the taken-for-granted logics or realities of the dominant culture, and shows how they support the self-interest of the dominant groups and perpetuate injustice. Critical race theory in the United States has drawn public attention in its exploring the racist implications embedded in ordinary social conventions and institutions. As argued, for example, institutions of justice, education, and health systematically penalize the Black communities. Laws said to protect voting security actually function as a means of suppressing the minority vote. National educational tests, used by policy makers ‘to ensure that everyone has an equal chance,’ actually reward those who are financially and academically privileged. We shall return to the implications of ideological critique shortly. In the meantime, we turn to a second intellectual wellspring for constructionist work.

언어적 비판: 현실과 이성을 텍스트로서 바라보기

당신이 단 10개의 단어만 사용해서 자신의 삶의 이야기를 전해야 한다고 상상해 보세요. 이 10개의 단어는 당신이 자신의 삶에 대해 말할 수 있는 모든 것을 제한합니다. 혹은 원하는 만큼 많은 단어를 사용할 수 있지만, 자신을 지칭하는 단어(I, me, mine 등)는 사용할 수 없다고 한다면 어떨까요? 이러한 단어 없이 당신의 삶의 이야기는 어떻게 될까요? 여기에서 우리는 정확한 서술의 어려움을 이해하기 시작할 수 있습니다. 세상을 표현하는 도구는 우리가 세상에 대해 말할 수 있는 것을 제한하거나 안내합니다. 이러한 함의는 매우 광범위합니다. 이를 탐구하기 위해 먼저 스위스 언어학자 페르디낭 드 소쉬르(Ferdinand de Saussure, 1857-1913)의 초기 영향력 있는 저작을 살펴보는 것이 유용합니다. 소쉬르는 그의 영향력 있는 저서 일반언어학 강의(Course in General Linguistics)에서 우리가 소통하는 체계를 연구하는 학문, 즉 기호학의 논리를 제시했습니다. 여기에서 두 가지 아이디어가 특히 중요합니다.

첫째, 소쉬르는 기표(signifier)와 기의(signified)를 구별하며, 기표는 단어(또는 기타 신호)로 작용하고, 기의는 단어에 의해 지시되는 것(단어가 나타내는 대상)을 의미한다고 설명했습니다. 따라서 우리는 여기서 대상(기의)과 그것을 이름 짓는 데 사용하는 단어(기표)를 갖게 됩니다. 소쉬르가 제안한 바와 같이, 기표와 기의 사이의 관계는 궁극적으로 임의적입니다. 이는 앞서 언급된 구성주의적 명제와 유사한 점을 가집니다. 즉, 세상은 우리가 그것에 대해 어떻게 말해야 하는지 요구하지 않습니다. 원칙적으로 우리는 어떤 기표를 사용해서도 어떤 기의를 지칭할 수 있습니다. 단순한 예로, 부모님이 당신에게 다른 이름을 지어줄 수도 있었고, 우리가 '중력'이라고 부르는 것을 '신의 의지'라고 부를 수도 있다는 것입니다.

둘째, 소쉬르는 기호 체계가 고유한 내부 논리에 의해 지배된다고 제안했습니다. 단순한 예로, 언어에는 문법이나 구문과 같은 사용 규칙이 있습니다. 우리가 말하거나 글을 쓸 때 이러한 규칙(내부 논리)을 따라야 합니다. 그렇지 않으면 의미를 전달하지 못할 것입니다. 여기서 비트겐슈타인의 '언어 게임' 개념과 그것이 우리가 말하는 방식에 요구하는 것을 떠올릴 수 있습니다. 의미를 만들려면 규칙을 따라야 합니다. 우리는 '있는 그대로의 세상'을 자유롭게 묘사할 수 없습니다.

The Linguistic Critique: Reality and Reason as Text

Consider your frustration if you tried to tell your life story with a vocabulary of only ten words. These ten words would be the limits of all you could say about your life. Or, what if you could use all the words you wanted, except those referring to yourself – for example, I, me, mine? What would your life story be without such words? Here you can begin to appreciate the difficulty of accurate description. The tools of representing the world limit or guide what we can say about it. The implications are far reaching. To explore, it is first useful consider the early and influential writings of the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913). In his influential volume Course in General Linguistics Saussure laid out the rationale for what became the discipline of semiotics, that is, a science focused on the systems by which we communicate. Two of his ideas are particularly important to our discussion.

First, a distinction is made between the signifier and the signified, with the signifier serving as a word (or some other signal) and the signified designating that which is signalled by the word (that for which it stands). Thus, we have here an object (the signified) and a word we use to name it (the signifier). As Saussure proposed, the relationship between signifiers and signifieds is ultimately arbitrary. The point here is similar to the first constructionist proposition above: the world makes no demands as to how we talk about it. We can, in principle, use any signifier to refer to any signified. On a simple level, your parents could have given you another name; more interestingly, what we call ‘gravity’ could also be called ‘God’s will’.

Saussure’s second significant proposal was that sign systems are governed by their own internal logics. On a simple level, languages have rules of usage, such as rules of grammar or syntax. When we speak or write we must approximate these rules (or internal logics); otherwise we will fail to make sense. You will recall here Wittgenstein’s concept of the language game and the demands it makes on how we talk. Making sense is a matter of following the rules. We are not free to describe ‘the world as it is’.

언어의 제약에 대한 이러한 우려는 문학 이론 분야에서 극적으로 확장되었습니다.

사실, 인간의 이성이라는 개념 자체가 의문에 부쳐졌습니다. 데카르트부터 현재까지, 이성은 서구 문화에서 소중히 여겨졌으며, 근대주의 세계관의 핵심 미덕으로 간주되어 왔습니다. 우리는 이성이 인간을 다른 동물들보다 우위에 있게 하며, 인간 생존에 필수적이라고 믿도록 교육받습니다. 하지만 문학 연구는 다른 관점을 제시합니다. 특히 프랑스 문학 이론가 자크 데리다(Jacques Derrida)의 반론이 중요합니다. 데리다의 저술은 흔히 해체주의(deconstructionist)로 알려져 있으며, 모호하고 다양한 해석을 허용합니다. 그러나 한 관점에서는, 그의 논의는 인간 이성에 대한 문화적 신뢰를 심각하게 약화시킵니다. 두 가지 주요 전제를 고려해 보겠습니다.

첫째, 데리다는 이성적 논증이 의미의 대대적인 억압을 초래한다고 주장합니다. 간단히 말해, 이성적 논증에 설득될 때 우리는 더 많이 알게 되는 것이 아니라 오히려 덜 알게 된다는 것입니다.

둘째, 모든 이성적 논증은 면밀히 조사하면 결국 무너진다고 주장합니다. 따라서 이성은 어떤 것도 – 예를 들어 정부와 과학의 제도, 또는 도덕적이거나 가치 있는 것을 결정하는 방식 – 기반이 될 수 없습니다. 오히려 데리다는 우리의 '타당한 이유'가 결국 억압적이며 공허하다고 주장합니다. 이는 강력하고 심지어 충격적인 결론입니다. 어떻게 이러한 결론을 방어할 수 있을까요?

먼저, 어떻게 이성이 억압을 초래하거나 우리의 시각을 좁힌다고 결론내릴 수 있을까요?

데리다는 먼저 언어를 차이의 체계로 봅니다. 즉, 언어는 각각 다른 모든 단어와 구별되는 단어들로 구성됩니다. 이러한 차이를 형식적으로 논의하는 방식 중 하나는 이항(binary)으로 설명하는 것입니다(둘로 나누는 방식). 즉, 단어의 고유성은 '그 단어'와 '그 단어가 아닌 것'(즉, 다른 모든 단어) 간의 단순한 구분에 의존합니다. 예를 들어, '흰색(white)'의 의미는 '흰색이 아닌 것'(예: '검은색(black)')과의 차이를 통해 정의됩니다.

따라서 단어의 의미는 존재(사용된 단어)와 부재(대비되는 단어들) 간의 차이에 의존합니다. 언어에서 의미를 만든다는 것은 존재를 설명하거나 지칭하는 방식으로 말하는 것입니다. 그러나 동시에, 부재는 배경으로 밀려나거나 심지어 의식에서 사라질 수도 있습니다. 존재는 단어 자체에 의해 초점으로 끌어올려지는 반면, 부재는 단지 암시적으로만 존재하거나 아예 잊혀질 수 있습니다. 하지만 주목해야 할 점은 이 존재가 부재 없이는 의미를 가지지 못한다는 것입니다. 이항적 구분 없이는 그것들은 아무 의미도 가지지 못합니다.

This concern with the constraints of language was dramatically extended in the field of literary theory.

Indeed, the very idea of human reasoning was thrust into question. From Descartes to the present, reason has been prized in Western culture, standing as the chief virtue of the modernist world-view. As we are led to believe, it is the power to reason that sets humans above the remainder of the animal kingdom, and is essential for human survival. Literary study suggests otherwise. Among the most important objections are those of the French literary theorist Jacques Derrida. Derrida’s writings, often identified as deconstructionist, are ambiguous and open to many interpretations. From one perspective, however, they significantly undermine the cultural investment in human reason. Consider two major premises.

First, suggests Derrida, rational arguments bring about a massive suppression of meaning. Broadly put, when we are convinced by a rational argument we do not know more, but less.

Second, if closely examined, all rational arguments will collapse. Rationality, then, is not a foundation for anything – for our institutions of government and science, for example, or as a way of deciding on what is moral or worthwhile. Rather, Derrida suggests, our ‘good reasons’ are in the end both suppressive and empty. These are strong, even outrageous, conclusions. How can they be defended?

First, how can one conclude that rationality invites suppression, or narrows our views?

Like many others, Derrida first views language as a system of differences, a system in which each word is distinct from all others. Simply put, language is made of separate words, each distinct from all others. A formal way of talking about these differences is in terms of binaries (the division into two). That is, the distinctiveness of words depends on a simple split between ‘the word’ and ‘not the word’ (or all other words). The meaning of ‘white’, then, depends on differentiating it from what is ‘non-white’ (or ‘black’, for instance).

Word meaning thus depends on differentiating between a presence (the word you have used) and an absence (those to which it is contrasted). To make sense in language is to speak in terms of presences, what is described or designated. However, simultaneously thrust into the background, possibly out of consciousness, are the absences. As you can see, the presences are privileged; they are brought into focus by the words themselves; the absences are only there by implication. Or, we may simply forget them altogether. But take careful note: these presences would not make sense without the absences. Without the binary distinction they would mean nothing.

이 논리를 실제로 적용해 보겠습니다:

우리가 널리 받아들이는 과학적 관점에 따르면, 우주는 물질로 이루어져 있습니다. 따라서 인간도 본질적으로 물질적 존재입니다. 우리가 이 물질을 뉴런, 화학적 요소, 또는 원자로 표현하든 간에 말입니다. 만약 물질이 제거된다면, 남아 있는 것은 인간이라고 부를 수 있는 것이 아무것도 없게 됩니다. 인문학자와 영성주의자들은 이 관점에 깊은 우려를 표합니다. 이는 우리가 인간에 대해 가치 있다고 여기는 많은 것을 부정하기 때문입니다. 우리는 인간의 삶이 자동차나 컴퓨터보다 더 큰 가치를 지닌다고 믿고 싶어 합니다. 그러나 물질주의적 세계관은 너무나 자명하게 보입니다! 주변을 둘러보십시오. 물질 외에 다른 것이 존재하나요?

하지만 이제 해체주의자의 주장을 고려해 봅시다.

'물질(material)'이라는 단어는 오직 이항적 대조, 즉 '비물질(non-material)'과의 대비를 통해서만 의미를 가집니다. 이를 물질/정신(material/spirit)이라는 이항으로 생각해 보십시오. '우주는 물질로 이루어져 있다'는 말은 정신과 구분되지 않는다면 의미가 없습니다. 따라서 물질이 무엇인지 말하기 위해서는 정신으로 식별 가능한 무언가가 반드시 존재해야 합니다. 그러나 만약 정신이 물질에 어떤 의미를 부여하기 위해 존재해야 한다면, 우주는 완전히 물질로만 이루어질 수 없습니다. 다시 말해, 물질주의적 세계관에서는 정신적 세계가 주변화되어(페이지의 눈에 띄지 않는 가장자리로 밀려나) 있습니다. 정신은 말로 표현되지 않은 부재입니다. 하지만 이 부재가 없다면, '우주는 물질로 이루어져 있다'는 의미 자체가 파괴됩니다. 즉, 물질주의적 세계관 전체는 정신의 억압 위에 성립되어 있습니다.

이제 두 번째 제안으로 돌아가 보겠습니다.

이성적 논증을 면밀히 검토하면 그것은 공허하다는 주장입니다. 왜 이런 결론에 이르게 될까요? 다시 언어를 자족적 체계로 간주하는 아이디어로 돌아가 봅시다. 여기서 각 용어의 의미는 다른 용어들과의 관계에 따라 결정됩니다. 데리다의 주장에 따르면, 이 관계는 두 가지 구성 요소, 차이(difference)와 연기(deferral)로 이루어질 수 있습니다. 첫 번째 경우, 단어는 다른 단어와 다름으로써 의미를 얻습니다. 이를 앞서 이항적 대조로 논의했습니다. 예를 들어, 'bat'이라는 단어는 자체적으로는 아무 의미도 없으며, 'hat'이나 'mat' 같은 다른 용어들과의 대비를 통해서만 의미를 가집니다. 하지만 이러한 대비만으로는 'bat'의 의미를 여전히 알 수 없습니다. 그 의미를 이해하기 위해서는 정의가 필요합니다. 즉, 우리는 'bat'이 무엇을 의미하는지 알려줄 다른 용어들에 의존해야 합니다.

사전을 참고하면, bat는 '공을 치는 도구', '무언가를 치다', '눈꺼풀을 깜빡이다(“batting an eye”)', '날아다니는 포유류' 등으로 다양하게 정의됩니다. 이제 문제가 생깁니다. 이 정의들의 의미는 무엇인가요? 예를 들어, 사전은 '날다(flying)'를 '공중을 통해 움직이다(moving through the air)' 또는 '성급한(hasty)'이라고 정의합니다. 그런데 이 용어들은 또 무엇을 의미하나요? 간단히 말하면, 사전의 모든 항목은 다른 단어들로 정의되어 있으며, 따라서 각 단어는 정의를 읽기 전까지 그 의미를 미룹니다. 단어의 의미를 찾으려 하면 우리는 사전 속에서 끝없는 탐색으로 내몰리게 됩니다. '실재'로 나가는 출구는 없습니다.

또한 순환 정의도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 사전에서 '이성(reason)'의 의미를 찾으면 종종 '정당화(justification)'라고 나옵니다. '정당화'를 다시 찾아보면 '이성(reason)'으로 정의됩니다. 이제 스스로 물어보십시오. 이 정의의 순환 밖에서 '이성'은 무엇인가요?

Let’s put this argument into action:

Consider the widely accepted scientific view that the cosmos is made up of material. We, as humans, then, are essentially material beings – whether we speak of this material in terms of neurons, chemical elements, or atoms. Take away the material and there is nothing left over to call a person. Humanists and spiritualists are deeply troubled by this view, as it repudiates much that we hold valuable about people. We want to believe there is something that gives human life more value than an automobile or a computer. Yet, materialism as a world-view seems so obviously true! Look around you; is there anything but material?

But now consider the deconstructionist’s arguments: the word ‘material’ gains its meaning only by virtue of a binary, that is, in contrast to ‘non-material’. Consider this binary in terms of material/spirit, for example. To say, ‘the cosmos is material’ makes no sense unless you can distinguish it from what is spirit. Something identifiable as spirit must exist, then, in order to say what material is. Yet, if spirit must exist in order to give material any meaning, then the cosmos cannot be altogether material. To put it another way, in the world-view of materialism, the spiritual world is marginalized (thrust into the unnoticed margins of the page). The spirit is an unspoken absence. However, without the existence of this absence, the very sense of ‘the cosmos is material’ is destroyed. As one might say, the entire world-view of materialism rests on a suppression of the spirit.

Now let’s turn to the second proposal: when rational arguments are placed under close scrutiny, they fall empty. How is this so? Return again to the idea of language as a self-contained system, where the meaning of each term depends on its relationship to other terms. As Derrida proposes, we might see this relationship as made up of two components, difference and deferral. In the first case, a word gains its meaning by virtue of differing from other words. We just discussed this in terms of binaries. In effect, a word like ‘bat’ has no meaning in itself, but only when contrasted with other terms, such as ‘hat’ or ‘mat’. However, these contrasts still leave us ignorant of the meaning of ‘bat’. In order to understand the term we need a definition. That is, we must defer to other terms that will tell us what ‘bat’ means.

If we consult a dictionary, we find that bat can be defined variously as ‘an implement for hitting a ball, ‘to hit at something’, ‘to flutter one’s eyelids’, as in “batting an eye’, ‘a flying mammal’ and so on. Now we face a problem. What is the meaning of these definitions? For example, the dictionary defines ‘flying’ as a ‘moving through the air,’ or as ‘hasty,’ but what then do these terms mean? To put bluntly, every entry in the dictionary is defined in terms of other words, and thus, each word defers its meaning until you read its definition. When we search for the meaning of a word, we are thrust into an endless search through the dictionary. There is no exit to ‘the real’. And then there are the tautologies: for example, if you search the dictionary for the meaning of ‘reason’, you will often find that it is ’a justification’. If you then look up ‘justification’, it will be defined as ‘reason’. Now ask yourself, what is reason outside this circle of mutual definition?

이 주장을 비판적으로 살펴보기 위해, 예를 들어 ‘민주주의’라는 용어를 고려해 봅시다.

우리는 민주주의를 소중히 여기고, 연구하며, 이론화하고, 필요할 경우 인간의 생명을 걸어서라도 보호해야 하는 정부 형태로 이야기합니다. 하지만 '민주주의'라는 용어의 의미는 단순히 사람들이 움직이는 모습을 관찰함으로써 도출되지 않습니다. 이 단어는 사람들의 행동을 묘사한 그림이 아닙니다. 오히려 이 용어를 의미 있게 사용하려면 '민주주의'와 '전체주의', '군주제'와 같은 대조적 용어들 간의 문학적 구별에 의존해야 합니다. 그리고 이러한 용어들의 정의는 다른 단어들에 다시 의존하며, 이러한 과정은 계속됩니다.

명확성을 위해, 민주주의를 '자유'와 '평등'이라는 용어로 정의한다고 가정해 봅시다.

하지만 이 두 용어는 정확히 무엇을 의미하나요? '자유'나 '평등'은 무엇인가요? 명확성을 얻기 위해, 우리는 다른 용어들로 연기(deferral)합니다. 예를 들어, '평등'은 '불평등'의 반대이며, '공정'하고 '정의로운' 사회에서 반영된다고 말할 수 있습니다. 하지만 '불평등'은 정확히 무엇이고, '공정'이나 '정의로움'은 무엇을 의미하나요? 이 탐색은 계속되며, 민주주의에 관한 자기 참조적 텍스트를 떠나 '실체 그 자체'를 만나는 방법은 없습니다. 민주주의의 의미는 근본적으로 결정 불가능(undecidable)합니다.

요약하자면, 이성적 논증으로 제시되는 모든 것은 억압적이면서 근본적으로 모호하다고 말할 수 있습니다.

논증은 그 의미를 구성하는 데 필수적인 반대편의 목소리를 포함하여 모든 다른 목소리를 침묵시킵니다.

그리고 설령 자신감 있게 주장된다고 해도, 논증은 심각한 취약성을 감춥니다. 이는 논증을 구성하는 모든 용어가 깊이 모호하다는 사실 때문입니다. 명료성과 자신감은 단지 너무 많은 질문을 하지 않는 한 유지될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, '민주주의란 정확히 무엇인가? … 정의란? … 전쟁이란? … 사랑이란? … 우울이란?'과 같은 질문입니다. 면밀히 조사하면, 모든 권위 있는 논증은 무너지기 시작합니다. … 지금 당신이 읽고 있는 논증을 포함해서 말입니다!

To give these arguments a critical edge, consider a term such as democracy.

We speak about democracy as a form of government to be cherished, studied, theorized, and if necessary, protected with human life. Yet, the meaning of the term ‘democracy’ is not derived from our simply observing people moving about. The word is not a picture of people’s actions. Rather, to use the term meaningfully depends on a literary distinction between ‘democracy’ and such contrasting terms as ‘totalitarianism’ and ‘monarchy’. And the definition of these terms depends, in turn, on other words, and so on.

To gain clarity, let’s say you define democracy in terms of ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’. Yet what do these latter terms mean? What exactly is ‘freedom’ or ‘equality’? For clarity, we defer to other terms. ‘Equality’, we might say, is the opposite of ‘inequality’; it is reflected in societies that are ‘fair’ and ‘just’. But what precisely is ‘inequality’, and what is it to be ‘fair’ or ‘just’? The search continues, and there is no means of exiting the self-referring texts of democracy to encounter ‘the real thing’. The meaning of democracy is fundamentally undecidable.

To summarize, one might say that whatever is put forth as a rational argument is both suppressive and fundamentally ambiguous. The argument silences all other voices, including the opposition whose existence is essential to its sense. And even if asserted with confidence, the argument masks a profound fragility – the fact that all the terms making up the argument are deeply ambiguous. Clarity and confidence can be maintained only as long as one doesn’t ask too many questions, such as ‘what exactly is democracy … justice … warfare … love … depression?’ and so on. When examined closely, all authoritative arguments begin to collapse … including the one you are now reading!

사회적 비판: 어떤 공동체가 발언하고 있는가?

앞서 논의된 두 가지 비판적 운동 – 세계에 대한 모든 설명에 내재된 가치 함의를 지적하는 운동과, 우리의 언어가 세계에 대한 설명을 제한하는 방식을 지적하는 운동 – 은 현대 구성주의(constructionism)에 기초적인 기여를 했습니다. 그러나 세 번째 운동은 아마도 가장 광범위한 영향을 미쳤을 것입니다. 이 운동은 효과적으로 과학적 지식의 토대를 도전했습니다. 또한, 이 운동은 앞선 두 운동의 주요 제안을 포함합니다.

현대 과학은 종종 서구 문명의 최고 업적으로 여겨집니다. 자랑스러운 사실로, 과학은 단순한 의견, 취향, 주관적 가치의 혼돈과 대조를 이룹니다. 과학자들은 확실한 사실(hard facts)을 가지고 있습니다. 안락의자에 앉아 하는 추측과 달리, 과학자들은 의료 치료제, 로켓, 원자력과 같은 실제 세상에 영향을 미치는 결과물을 만들어냅니다. 이러한 과학 지식에 대한 찬양으로 인해, 과학은 교육 커리큘럼, 국가 정책 결정, 범죄 조사, 군사 계획 등에서 중요한 역할을 합니다. 종교적, 정치적, 윤리적 권위에 대한 다른 주장들과 달리, 과학적 권위는 거의 의문을 받지 않습니다.

바로 이러한 이유 때문에, 과학적 진리에 대한 구성주의적 도전은 광범위한 결과를 가져왔습니다.

처음에 많은 구성주의자들은 과학이 사회에 미치는 부정적인 영향에 주목했습니다. 예를 들어, 과학이 사회적 평등에 미치는 영향을 생각해 보십시오. 계몽 사상은 모든 개인에게 이성적 의견의 정당성을 부여함으로써 매우 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 현실과 선에 대해 판단할 특권을 지닌 왕족과 종교의 권위는 제거되었습니다. 시간이 지나면서 과학은 이성에 대한 평등한 권리의 모델이 되었습니다. 과학 세계에서는 누구나 독립적인 관찰의 특권을 가질 수 있습니다. 엄격한 조사 방법을 따르는 사람은 누구나 청중 앞에서 발언할 권리를 갖습니다. 이는 훌륭한 아이디어입니다.

하지만 이제 생각해 보십시오. 독자로서 당신은 '다원자 분자의 PE 표면’, '시클로펜테인-1,3-디일의 불확정성’, 또는 'Hox 유전자’에 대해 무엇을 말할 수 있습니까? 아마도 당신은 이들에 대해 의견이 없을 것이며, 이러한 주제에 대해 거의 알지 못할 가능성이 큽니다. 더구나, 이 표현들조차 제대로 이해하지 못할 수 있습니다. 따라서 당신은 이러한 보고서들의 진실을 받아들일 수밖에 없습니다. 비평가들은 이를 위험한 상태로 봅니다. 이는 다시 과학자의 목소리와 가치를 제외한 모든 것을 배제하는 상황을 만들어냅니다. 아이러니하게도, 평등의 보루로 여겨지는 이 상태가 이제는 평등을 제거하는 기능을 한다고 할 수 있습니다. 모든 목소리가 동등하지 않습니다. 이것이 새로운 고위 성직자 계층의 출현과 같으며, 누구도 의문을 제기할 수 없는 권한을 지닌 은밀한 독재와 동등한가요?

The Social Critique: Which Community Is Speaking?

The two critical movements just discussed – the one pointing to the value implications in all accounts of the world, and the other to the way in which our language limits our accounts of the world – are seminal contributions to contemporary constructionism. However, a third movement was perhaps the most broad-sweeping in impact. This movement effectively challenged the foundations of scientific knowledge. It is also a movement that incorporates the major proposals of the first two movements.

Modern science is often viewed as a crowning achievement of Western civilization. As boasted, the sciences stand in contrast to the chaos of mere opinions, tastes and subjective values; scientists have the hard facts. In contrast to armchair speculation, scientists produce real-world effects: medical cures, rockets, and atomic power. Because of this adulation of scientific knowledge, such knowledge plays a major role in educational curricula, national policy making, criminal investigation, military planning, and more. Unlike other claims to authority – religious, political, ethical – scientific authority is seldom questioned.

It is precisely for these reasons that the constructionist challenge to scientific truth has been far-reaching in its consequences.

At the outset, many constructionists have been concerned with the negative effects of science on society. Consider, for example, the implications of science for social equality. Enlightenment thinking was vastly important in terms of its granting the legitimacy of reasoned opinion to each and every individual. The privilege of royalty and religion to rule on the nature of the real and the good was removed. Over time science became the model for equal rights to reason. In the scientific world, everyone has the privilege of independent observation. Anyone who follows the rigorous methods of investigation has the right to an audience. Good ideas, for sure.

But now consider: what do you as reader have to say about the ‘PE surface for polyatomic molecules’, ‘the indeterminacy of cyclopentane-1,3-diyl’, or ‘Hox genes’? Chances are you have no opinion; you know little about such matters. Moreover, you may scarcely understand the phrases. Thus, you are forced to accept the truth of these reports. Critics view this as a dangerous condition, as it again removes the voices and values of all but the scientist’s. Ironically, one might say that this bastion of equality now functions to remove equality: all voices are not equal. Is this equivalent to the emergence of a new breed of high priests, a subtle dictatorship with powers beyond anyone’s questioning?

이러한 무비판적인 권력의 위험성은 많은 학자들이 과학적 지식을 비판적으로 분석하게 만드는 원동력이 되었습니다.

그들의 작업은 과학적 노력을 약화시키려는 것이 아니라, 과학의 무비판적인 권위를 제거하고 그것을 일상적인 검토의 영역으로 끌어들이는 것이 목적이었습니다. 비판의 주요 초점 중 하나는 세계에 대한 과학적 설명이었습니다. 특정한 묘사와 설명의 언어가 어떻게 다른 언어들보다 선택되었는지에 관한 것이었죠. 세상을 있는 그대로 묘사하는 데 있어 특정 단어 배열이 특별히 우선시될 이유는 없음을 상기하십시오. 무수히 많은 설명이 가능하기 때문입니다.

특히 중요한 점은, 과학자들이 진리를 주장하기 때문에 그들의 설명은 사회로 스며들어 사회가 세상을 이해하는 방식을 형성한다는 것입니다.